After 40 years in the wilderness, Hunt Sales gets his life and his music together

After 40 years in the wilderness, Hunt Sales gets his life and his music together

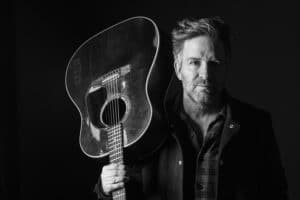

The drummer whose iconic beats kick off the Iggy Pop classic “Lust for Life,” as well as half of the rhythm section of David Bowie’s 1990s project Tin Machine, is by no means a made man. He works daily and is struggling to scrape together the cash necessary to mount a small tour behind his new record, “Get Your Shit Together,” credited to the Hunt Sales Memorial. Much of his contributions to a number of artists over the past four decades — from Pop and Bowie to Todd Rundgren to the ’70s power trio Paris to Charlie Sexton — make for an impressive resume but have yielded little in the way of financial dividends.

Despite all of that, however, he’s in a better place than he ever was. After all, he’s on the right side of the dirt, a minor miracle given everything he put his body through while in active addiction. There are dozens of peers who came of age during the hedonistic era of ’70s and ’80s rock ‘n’ roll who are not, and Sales counts himself as one of the survivors, he told The Ties That Bind Us recently.

“If you look online, the life expectancy of an IV drug user is usually 10 to 15 years, and I outlived that by about 40 years,” he said. “I had a period of sobriety about 12 years ago, and I did a bunch of work. I worked the Steps, I had a sponsor, and a few things changed in my life immediately. I was in Nashville, and everybody there was drinking or smoking weed, and (recovery) kept me out of a lot of circles. I spent one year there, then I came back to Austin, where I eventually went back to my old behavior.

“It just gets worse every time. I finally had that moment of clarity — do I want to live, or do I want to die? Sometimes I wonder why it took so long, and why now, but I don’t know, and it really doesn’t matter. I don’t have all these answers. All I know is that in the 15 months I’ve been clean, I haven’t put a needle in my arm, and that’s a big thing for me.”

From Tony to Todd to Iggy

He and his brother became quasi-teen idols as part of the band Tony and the Tigers, which had a minor radio hit in the Detroit area and made a couple of TV appearances in 1965. Five years later, the brothers switched gears and teamed up with Rundgren for his album “Runt,” adding a loping, languid beat to the radio hit “We Gotta Get You a Woman.” After that, they played around Los Angeles, where everyone seemed to dabble in extracurricular substances, Sales said.

“I don’t remember my mom and dad sitting me down and saying, ‘You’re gonna run a habit, you’re gonna be a criminal, you’re gonna do some (messed up stuff),” he said. “I hated needles as a kid, but I still became an IV drug user.”

Ironically, Sales became the driving force — again, literally — behind Pop’s upbeat ode to the drug culture. “Lust for Life” was Pop’s second collaboration with Bowie; in early 1977, the pair had worked on “The Idiot,” and upon completion of a support tour, they assembled the “Lust for Life” team that included the Sales brothers.

“I first met David back in ’72 or ’73, whenever he was doing the Ziggy Stardust stuff, and I went to see him play at Radio City, and I eventually got to know him through Iggy,” Sales said. “Iggy called us up to tour behind ‘The Idiot,’ and then we made ‘Lust for Life.’”

The Sales brothers stuck around through “TV Eye Live 1977,” and in the 1980s, Hunt contributed to a number of projects, including film soundtracks and work by other musicians, when his brother called him up, inquiring about another collaboration with Bowie. The mercurial Englishman had found mainstream fame with the 1983 “Let’s Dance” album, but subsequent work with guitarist Reeves Gabrels went in a more experimental direction. At the 1987 conclusion of his “Glass Spider” tour, he and Gabrels wanted to get back to basics, and recalling the bombast the Sales brothers had given Pop’s albums, he reached out about a new band: Tin Machine.

A rock 'n' roll supergroup

Tin Machine: Tony Sales (from left), David Bowie, Hunt Sales and Reeves Gabrels.

“David was coming from a weird place, and he wasn’t sober yet, but to me, creatively, it was good,” Sales said. “At the time, everybody was wanting to hear him sing ‘Let’s Dance,’ and then here was me, probably his closest connection to the street and somebody who wasn’t a millionaire; just a working musician and a friend.”

The Sales brothers pushed Bowie into more spontaneous directions, and Tin Machine — a true democracy, with profits split four ways and all songs credited to each member — steered clear of pop, glam and art rock that had categorized Bowie’s career to date. The band’s debut was released in 1989, and label pressure immediately pulled Bowie back into solo artist mode; Tin Machine would release a second album in 1991, followed by a live record, but by 1993, the group had dissolved.

“It ran its course,” Sales said. “He had people around him steering him in other directions, and even though I had my problems back then, I always showed up and did my work regardless of whatever I was into. I had one writer tell me that David said we stopped Tin Machine because of my drug problem, but that’s a bunch of (crap). I made every gig; I made the records; I was there.

“I understand that behavior scares people, but that’s not why the band broke up. David was allowed to say whatever he wanted, but there are a couple of sides to every story.”

Sales spoke briefly with Bowie in the following years before the latter’s death in January 2016, “but there was kind of a bad taste in my mouth about a lot of the (stuff) that went down,” he added.

“But that’s my shit,” he said. “It’s always good to rise above that stuff, and I try to keep that in mind. It was a good band, and (the music) holds up well. Now, there’s a whole new audience for that stuff, and there’s Tin Machine stuff lying around dormant that no one’s heard. Hopefully, it will be released at some point.”

Whether he’ll get closure with Pop, however, remains to be seen. Sales is proud of the work he contributed, but he also feels he hasn’t been adequately compensated. “Lust for Life,” he pointed out, has been used liberally in commercial advertisements (Royal Caribbean Cruises made a series of famous commercials with it several years ago, for example), and he’s never been paid a dime of royalties.

Again, he tries to practice the spiritual principle around which the First Step is built: acceptance.

“(Living in it) is not good for me,” he said. “Regardless of what I’m owed and that guy not being cool and not throwing me something, that’s just the way it is, so I can’t live in that resentment.”

A drummer for all sounds

Heather’s support has been invaluable to his sobriety, which was the last house on the block when he came to the end of addiction’s road, he said.

“I got away for a long time using, despite getting infections all the time,” he said. “My veins went years ago. Twelve or 15 years ago, my doctor said, ‘If you’re ever in a car accident, you’re (screwed), because they won’t be able to put a line in you. I was diagnosed as a borderline diabetic a few years ago, but did I watch my health? No, so two years ago, I was diagnosed as a diabetic.

“I got to a point where I was running infections, one after the other, and I would get these abscesses that would either blow over or cook, so I would have to get on antibiotics for several days a week for years. I got to a point where I was just so infected, I even had dope sitting around but I couldn’t do it, because I was just sick and abscessed.”

It was a Tuesday when Sales decided to wave the white flag; the next day, he found a physician that put him on Medication Assisted Therapy for a few days, but within a week, he had to get back to work. The program had offered him a brief respite several years earlier, so he started going back to meetings. He worked the Steps. He got a sponsor. And the universe gave him a couple of atta-boys.

“I had been sober for about three months, and as you know, early sobriety is (messed) up — it’s not easy, but I worked really hard, and I wrote a bunch of new songs,” he said. “I wrote ‘One Day’ while I was at a friend’s house in Memphis, then came back to Austin and finished it up. I went back to Memphis, where I recorded six songs in one day, did all of the overdubs the next day and rough mixes on the third day. And I was doing gigs at night in Memphis to make money.”

A new way of life, and a new sound

Another six songs led to a full album, most of which was done with former Austinite Will Sexton, who had relocated to Memphis and invited Sales up to collaborate. Bruce Watson of Fat Possum/Legal Mess Records caught wind of the new material, paid a visit to the studio and solicited a single, which led to the Big Legal Mess release of “Get Your Shit Together” last month.

“I’m sitting here, not shooting dope at all, and I have a record out, but nothing else has changed much,” he said. After a pause, he adds: “Everything and nothing has changed.”

The album is a full-throttle rock ‘n’ roll wrecking ball, from the driving “Here I Go Again” to the country-tinged R&B bounce of “Angel of Darkness” to the mournful “One Day,” every song anchored by Sales’ voice, a whiskey-and-smack scarred thing that bears the hallmarks of a circus tiger: weary but possessive of a feral power and a primal ferocity that puts the listener on notice — whatever Sales has been through, he ain’t done yet.

More than anything else, it rings with an authenticity that’s an endangered species in popular music these days. Much of it comes from his life experience, and it’s no coincidence, Sales added, that the music that still resonates the most with him was made by men and women who have traversed similarly broken roads.

“Whether it’s Frank Sinatra or James Brown or whoever, they’ve been through some (stuff), and it comes through in feeling,” he said. “A lot of music out now, it’s got a feeling of anger and violence. I’m not saying it always has to be Sam Cooke, but somewhere close to that would be good. I just don’t get it, because it doesn’t move me.

“I remember I met this young black guy at a meeting; he was maybe 21, or he could have been 18, or 23 … I don’t know. But I asked him if he’d ever heard of Sam Cooke, and he said no, so I pulled him up on YouTube, and just listening to that, I felt like I was about to cry, man. Then he asked me if I had heard of some guy, and when I said no and asked what the deal was, he pulled up this video.

“And it’s just this guy cooking up rock in the kitchen,” Sales added. “It didn’t have a good melody; the song sucked. It was this video of a guy cooking up rock, and this kid had no idea who Sam Cooke was.”

A spot at the table for a rocker in recovery

“Life is a car crash; entertainment is a car crash,” he said. “There’s some good music out there, definitely, but there’s also a bunch of (crap). And there are people out there who recognize something good when they hear it, but they can’t get it, and instead they’re just getting (crap).

“I’m just trying to tell a few stories on my record. I’m writing new music and trying to support it, trying to get money together to get out on the road, but it’s rough, man. I think I’m gonna be able to pull it together in the next five months, so I could be out there doing a West Coast tour, all the way up to Seattle and Portland.”

It’s slowly coming together, and while he’s unsure if it’s a certainty, one thing he is sure of: It’ll be a lot easier to pull together without a $2,000-a-month habit.

“They say money doesn’t buy happiness, but those people don’t know where to shop,” he said with a gravelly chuckle. “I do know this: There are people out there with $10 million getting ready to jump off a 10-story building right now, and there’s a family of five living on the street in India, and they’re happy. As for me, I’m basically broke, but I’ve got a roof over my head, and I’m not shooting up dope today.

“I have the regular problems that other people have, but I’ve gotta do the work. Normal stuff is for normal people, but I’m not a normal person — I’m an addict, and I’ve gotta do what I gotta do to stay sober. I still go to meetings, and I’m still available for people that struggle, and that really is a miracle.

In the end, I signed up to be human — nothing more, nothing less,” he added. “Life is for the living, man.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories