Blues and soul singer Nakia trades survivor instincts for recovery skills

Blues and soul singer Nakia trades survivor instincts for recovery skills

Addiction presents in a number of different ways, but it always comes down to a single undeniable symptom: The afflicted use external substances to ease internal anguish.

“I never had a problem putting down any of the drugs I used,” Nakia told The Ties That Bind Us recently. “It was always about realizing that there was something deeper going on causing me to use, something I was trying to get away from. Figuring out what that was and figuring out how to get myself centered and on a more spiritual path was super important to me.

“I have real survivor instincts from childhood trauma that make me hyper-alert to anything that’s causing me negativity or stress or danger. I’ve always done that, since I was a kid, and I think that my using, and the behaviors around my using, were classic examples of that, until finally I went into survivor mode and realized, ‘You’ve got to figure this out, because you’re killing yourself and hurting other people … and on top of that, you could be so much better.’

“That was always in the back of my head, even when I was using,” he added. “Today, I just find whatever that is and remove myself from the situation or find ways to make it better.”

Escape by any means necessary

Growing up in Alabama, Nakia had a front row seat to the unraveling of his parents’ marriage, he said, but he found an escape by eating. He was 10 years old at the time.

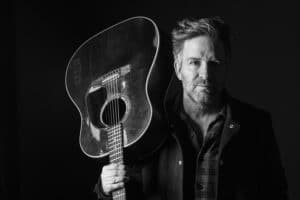

Courtesy of Nicolla Gell

“I really began to find comfort and learned how to change the way that I felt with food, long before I was ever turned onto any kind of real stimulants or anything,” he said.

By the time he was 13, he realized that drugs opened social doors, and that selling casual amounts meant he didn’t have to pay for it — a useful amenity for someone who was “poor and resourceful,” he said.

“I was doing most of that stuff even before high school, just helping other guys and gals I knew get high,” he said. “It never seemed like it was much of a problem for me, and it really wasn’t until I moved to Austin, after spending all of my teenage and adult life up to that point using in some form or fashion, that I really grasped the idea that I wasn’t aware what I had been doing to myself.”

He was what some people call a functional addict, meaning that while using was a welcome respite from reality, he was still able to maintain forward momentum. Credit some of that to his passion for music. There are moments from his past that Nakia remembers as pivotal when it comes to the way songs influenced his life and future career.

“When I got my first copy of ‘Destroyer,’ by KISS, or ‘August and Everything After,’ by Counting Crows,” he said. “That record came out at a time in my life when I was in a particularly creative space and state of mind, and it just really moved me. The songwriting really moved me. It’s another great example of somebody I’ve looked up to since I was a freshman in college, and somebody I would have never dreamed that I would have had some kind of connection to.

“Now, Adam (Duritz, Counting Crows’ singer) is a good friend, and I know several of the other members. Charlie (Gillingham), the keyboard player, has sat in with my band a couple of times, and I’ve sat in with the Crows a couple of times. It’s a full circle thing for me, because they continue to inspire me and make me want to be a better songwriter.”

A rebirth in Austin

Courtesy of George Hsu

In 1995, Nakia moved to Atlanta, eventually making his way to Chicago, where he worked as an intern at Aware Records before eventually landing in Austin, Texas, in 2002, the town he calls home today. Both respected and up-and-coming members of the Austin scene appreciated his powerhouse chops, and today, he’s grateful for the early connections he made.

“Alejandro Escovedo; Joe Ely; Tommy Shannon from Double Trouble; Miles Zuniga and Tony (Scalzo) from Fastball — a lot of them were all really super to me when I got here, and they really accepted me and took me under their wing, or at least let me bug them with questions, open shows, or hang out backstage and get to know people,” he said.

Credit that respect to his ability to move fluidly through a myriad of styles: As a kid, he cut his teeth on everything from Ray Charles to Prince to Journey, and when he takes the stage, he draws on a little bit of everything to reproduce a signature sound that earned him a place in Zuniga’s side project, the Small Stars. It wasn’t long after landing in Austin, however, that he began to take a hard look at his substance use, he said.

“I started asking questions of people I knew in recovery, just seeking out answers and looking for help,” he said. “That was in 2005, and I went to rehab, came home, worked steps and had a sponsor. I was very much a part of the local Austin community here, and I did pretty well, considering, as a musician who was sober and working in a business where one of my primary objectives was to sell alcohol.”

His relapse journey is a familiar one to a lot of folks in recovery who went back out and made it back: It started off innocuous enough, he said.

“I did very well, but at some point, as some folks do, I didn’t see quite the need to go to so many meetings, or do so much Step work, or be in touch with my sponsor and fellow addicts as much as I needed to be,” he said. “Eventually, I found myself needing to start fresh again, and it was kind of an off-and-on thing again for a few years.”

As much as “The Voice” changed his music career, it also changed his recovery trajectory, he said.

The price of fame

Courtesy of Martin do Nascimento

Sobriety had opened doors of opportunity for Nakia musically: He released an EP in 2007, started a band called the Southern Cousins and enjoyed regional success, opening for B.B. King, Willie Nelson and scoring a slot at the Austin City Limits Music Festival, among others. Escovedo tapped him to add guest vocals to his 2010 record, “Street Songs of Love,” and that same year, he put together a band called the Blues Grifters, which set fire to the Austin club circuit.

A video of that band’s performances made its way to noted TV producer Mark Burnett, who recruited Nakia for the debut season of “The Voice” in 2011. He selected Cee Lo Green as his coach and finished in seventh place; the show itself was a massive hit, and more than 14 million viewers tuned in every week. While some contestants try to distance themselves from their association with “The Voice,” Nakia has never had any regrets about taking part, he said.

“It’s a part of my story, and I loved it and thought it was great,” he said. “It’s not like it’s something I’m going to try and erase, but I’m really grateful for the opportunity, and I made a lot of really great friends — and certainly a lot of fans came from that, so I definitely wouldn’t trade that experience for anything. It gave me so much in terms of access to people, not just in the business, but more importantly in the people who are going to listen to and buy my records and come to the shows.”

Throughout his time on “The Voice,” he was sober, but once it was done and he returned home to Austin, things took a dark turn.

“I wasn’t being followed by a camera all the time, and I didn’t have someone telling me where to be or how to dress or at what time to be places, so I had a lot of free time on my hands,” he said. “The allure and reward of being on a No. 1 hit television show of that magnitude and being broadcast in front of millions of people and flown around the country to be on television and hearing my name on late-night TV, I think that was just as addicting as heroin is to some people. I think that left a real void in my life, and it got fairly dark there in the last half of 2011 and the first part of 2012, until I decided to take myself back to a meeting and started working Steps and recommitted myself to my recovery.”

The surrender always came with a moment of clarity, he added: the recognition that the continuing to use was the textbook definition of insanity, but being unable to stop doing so.

“Really, both times for me that I got clean and kind of packed it in and really surrendered it was really mostly just the real feeling of looking around and realizing just how good I already had it and not understanding why I had to keep doing these other things and acting these other ways, when everything else seemed to be going fine,” he said.

Full circle: A Grifter again

“It’s a project that really began after I left Alejandro Escovedo’s band in 2010, and I really decided that I wanted to take the advice of someone who was working on that project and do something that didn’t require a lot of effort and work on my part, so I formed a blues band,” he said with a chuckle. “I chose all these blues and soul covers to do, and I started playing shows, and it seemed to get popular pretty quick, and so we were making videos of our shows, putting them online, and it led, really, to ‘The Voice.’ ‘The Voice’ led to a bunch of other stuff, so it all kind of got put on hold, but really, it all started about seven years ago with some of the first tracks we cut.”

It’s a covers album, but it was cut on analog gear and with vintage microphones, which gives it a warmth and authenticity that’s palpable when Nakia’s voice comes pouring out of the speakers.

“It’s an homage to the people who wrote and recorded those songs originally, but it’s also an homage to the other grifters who came before me and did almost the exact same thing,” he said. “Look at the Stones, the Beatles, Zeppelin, The Yardbirds, the Allman Brothers, Boz Scaggs — so many people and artists who helped to bring the blues into a mainstream spotlight. I feel like that’s something that really needs to be done today, and you’ve got some people doing it, people like Jack White and the Black Keys who are making it on their own terms, but most of these songs are really traditional blues songs.”

Music is the second-most important thing in his life today — the first being, of course, his recovery. He makes himself available to help others with struggle as he once did, but more importantly, he wants to raise awareness of the problem — especially the toll that the music industry can take on struggling artists who might turn to external substances for internal solace.

“The music business has been in a constant state of flux for a long time, but now more than ever, music creators, whether they be songwriters or sidemen or producers, have to check so many boxes that we’re responsible for, things that nobody else is going to do,” he said. “Those things have dramatically increased, and I believe when you couple that with the crippling effects of social media and the way that it’s completely changed the relationship to the artist, it’s become really difficult for music creators to maintain any real semblance of free time. What’s more, there are very few boundaries between artists and fans or artists and clients or whoever that may be, and I feel like as far as emotional sanity goes, it’s really difficult for music creators to walk any kind of line that affords them time for themselves and turn out the work that affords them to do all that.

“And when you add in the stressors of addiction and the need for addicts to heal safe and also have the same levels of release that everybody else gets to have … when those don’t add up, I think we’re seeing more and more people who are turning to drugs for the first time, or finding themselves back there again. I see, especially in the Austin scene, a real sense of urgency of people freaking out and realizing there’s nobody to save them but themselves and not knowing where to turn to, and I think that’s pretty scary.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories