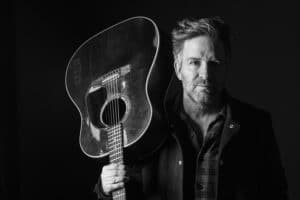

BUZZKILL: Recovering singer-songwriter Travis Meadows finds solace in the song

BUZZKILL: Recovering singer-songwriter Travis Meadows finds solace in the song

BUZZKILL: Recovering singer-songwriter Travis Meadows finds solace in the song

Singer-songwriter Travis Meadows isn’t a big believer in guardian angels, but there’s really no other way to describe the guy hanging out by the back door the last time he left treatment.

“I’d never seen him before, and I haven’t seen him since, but he said, ‘Where are you going?’ And I said, ‘I’m going home,’” Meadows told The Ties That Bind recently. “He said, ‘You should go to a meeting today,’ and I told him, ‘I’ve been in meetings for 30 days – I’m going home.’ And then he said, ‘Trust me: This will be the most important meeting of your life.’

“Minefield” would become the lead-off track to “Killin’ Uncle Buzzy,” released in 2011 and a searing documentation of a man coming to terms with his disease. From a troubled upbringing to restless youth to a present that had landed him in jails and institutions along the way to an early grave, he poured his guts into every song, writing as if his life depended on it. And in some ways, he said, it did.

“Writing that record, it was literally step by step, blow by blow, and it kept me so busy and so attentive to the process of not only detox but the getting-better stages,” he says. “It really kept me fully aware, and it kept me really busy, because it gave me something to do. All I was doing was going to write, going to meetings and going to the studio, and between those three things and being somewhat inspired, it kept me really busy.

“And really, it inspired me almost so hard that I almost didn’t think of it as inspiration, because it was so scary. I remember trying to go to sleep and having these really horrible nightmares, because your mind does really horrible things when you’re getting off that (stuff). I had to open my eyes, because I would forget where I was. There at the end, I was sleeping anywhere I could, from the back of a car, to treatment, to a one-room apartment, and I had to open my eyes to see something familiar and go, ‘It’s OK. I’m OK.’ I would get up at 3 in the morning and just hold my guitar like a security blanket, trying to get through the night.”

Painful beginnings

Courtesy of Joshua Black Wilkins

In the early days, those nights seemed interminable, but the sun always rose, just as it did on every other day of his life, even those filled with emotional pain that probably played a part in his addiction. His earliest memory, he’s recalled in previous memories, was of watching his brother drown. Raised by his grandparents, he lost most of his right leg to a cancer battle when he was 14. By then, he says, he had started experimenting. There’s no crystal-clear memory of when, exactly, chemicals sank their fangs into his young soul, but he remembers being 11 years old and sneaking his grandmother’s Valiums.

“There was some girl at school, and her mother was a nurse, and so she brought pills to school,” he says. “We didn’t know what they did; we just liked how they looked: ‘I like the yellows! I want the blues!’ That’s when I started hitting up the Valiums and smoking a lot of weed when I was a kid.”

Meadows grew up in Jackson, Miss., his voice still carries the inflection unique to the Magnolia State, a gentility that makes listeners hang on every word of his songs and the stories told between them. He started out playing the rounds at local bars and clubs, and when he was 21, he moved to East Tennessee and settled into the Gatlinburg area for a while. He picked up a guitar and started playing for tips at a nearby deli, teaching himself one cover song after another until he had well over 100. He started writing a few himself, but drugs and alcohol quickly took their toll before he had a literal come-to-Jesus moment.

“I turned into a preacher for 17 years, and that kind of held me off, but when that didn’t work anymore, I went back to drugs and alcohol, and it was just a six-year spiral,” he says. “It didn’t take long to realize that it wasn’t working at all, but it took me six years to get out.”

By that point, he’d moved to Nashville; while he enjoyed some early successes – a 2001 ASCAP Christian Music Award, eight Top 20 singles in the Contemporary Christian genre and a gig as a staff writer with Scott Gunter at Universal Music Publishing Group — the wheels quickly came off. He was arrested – twice – and in 2010, sitting before a jail nurse, he broke down.

“The first time in jail was a wake-up call – ‘I’m never gonna do that again!’ But then it happened again,” he said. “There were a lot of turning points, a lot of broken-heart moments, a lot of chaotic moments, but the biggest one was that second time in jail. They make you go to the nurse to make sure you’re healthy enough to be in there, and I remember sitting in there, and I just started crying, because I was absolutely panicking.

“She said, ‘Why are you crying?’ I told her I was an alcoholic, and she said, ‘You’re not an alcoholic!’ I told her to take my pulse, and it was 188 beats a minute. She said, ‘Oh my God! Take this pill!’ I was about to go into cardiac arrest right there in jail. It was horrible, so I got out, and I checked myself into rehab, hoping that it might help with the court date – and it did, but the difference was, I was not working the system. I was genuinely terrified and very angry with myself, and going to those meetings, whether it worked or not, I was in it for good.”

A new way to live

Courtesy of Joshua Black Wilkins

In 2010, he entered his fourth rehab for the last time, and come July, he’ll celebrate eight years sober. These days, famous artists like Eric Church and Jake Owen sing his praises, and thousands of not-so-famous people hang on every word of his songs, which are equal parts touching and heartbreaking. “Killin’ Uncle Buzzy” was Meadows at his most gut-level honest, with songs like “It Ain’t Fun No More” chronicling his descent into madness: “It ain't fun no more, can’t drink enough to get a good buzz, up it comes soon as I pour, fight it down but lose the war …” By the time the record was completed, he had nine months sober, which was an accomplishment in and of itself, he said.

“I had a bucket full of 24 hour coins, and a good handful of 30-day and 60-day chips, but I only have one or two six-month ones,” he says. “And I’ve only got that one nine-month one. It took six years to get nine months, and that was a big damn deal for me. Not too far into there, it seemed like somebody cut one of my songs, and that was life-changing. Things started lining up.”

He ended an unhealthy relationship and began to take his first tentative steps back into the clubs and bars that gave him a platform for his material. Like he did when he first ventured into the world newly sober, he depended on a network of other recovering addicts and alcoholics to steer him in the right direction, he adds.

“I made phone calls and asked, ‘Is this OK?’ And they’d tell me, ‘The fact that you’re calling and asking tells me the condition of your heart. If you’re doing everything right and by the book, it’s OK,’” he says. “So I started going out, and I was blown away to see people sober or just having a Coke, who were there for the music. And about the same time I started getting clear-headed was about the same time I started getting a handful of fans, too. I had them show up for support, and I would have my own little meeting within a show. Almost everywhere I go now, I’ve got a handful of sober people in every state, and it’s really beautiful.”

Calling for advice, or asking a friend to stay on the phone while he drove past convenience stores and bars on the way to the studio, was a humbling experience – but after a six-year run and a lifetime of pain, Meadows found himself too spiritually, emotionally and physically exhausted to try saving his face and his life at the same time.

“All of those little one-line slogans that almost feel like they’re speaking down to you? They might sound stupid, but they work,” he says. “If people make some suggestions, it’s because they’ve sat in those very chairs you’re sitting in. One of the big ones I keep coming back to is, ‘It works if you work it.’ That, and ‘keep coming back.’

“Just follow the suggestions, and don’t do things your own way. It gets better, and in the beginning, if they’d told me to stand in a corner and make gurgling sounds, I would have done it. I was just so beat down that I didn’t care.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories

BUZZKILL: Recovering singer-songwriter Travis Meadows finds solace in the song

BUZZKILL: Recovering singer-songwriter Travis Meadows finds solace in the song