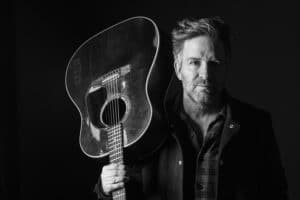

Celebrated songwriter Buddy Causey: ‘It’s not about me’

Celebrated songwriter Buddy Causey: 'It's not about me'

During his heyday, the Tennessee-born, Alabama-raised singer recorded with the greats in Muscle Shoals. He’d played with some of the top talent on the West Coast when he moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s. He even opened for Alan Jackson and Shania Twain in front of a crowd of 300,000 people.

But when he was 61, he suffered a stroke that “snapped an artery in two places in the back of my neck,” he told The Ties That Bind Us recently, and his world fell apart.

It’s been a long and winding road back to the stage, but these days, he’s not aiming for Billboard singles or million-selling albums. He just wants to change a few lives and share the grace that’s been granted to him.

“I’ve covered about seven states, playing at Celebrate Recovery meetings three, sometimes four nights a week,” he said. “I don’t make a nickel, other than it being the right thing to do.”

The journey begins

“I did local bands, and then I heard they made records up in Muscle Shoals, so I went up there when I was 19,” he said. “I did a medley of ‘Hey Baby’ with Quin Ivy (a noted Muscle Shoals record producer), which sold 60,000 or 70,000 copies in a month in North and South Carolina, because it was a beach music song. We went up there, and they almost killed us because that was the only beach music we had!”

It was the start of a busy career, however, that kept him on the road with United Artists for three years, after which time he moved to L.A. and signed to Capitol Records. With both the Buddy Causey Band and the Handsome White Boys, he started touring the country and even overseas. He also started experimenting more and more with drugs, he said.

“When I got to L.A., there were people there who tried to sell me drugs, but then after I started playing out there in the L.A. scene, they started giving me drugs,” he said. “Smoking pot and chasing women were my two biggest addictions, and after a couple of years, I was spiraling fast and furious down the rabbit hole. My life wasn’t worth a flip.”

When he turned 35, he quit for a while, but a new and tumultuous relationship pulled him back in. He continued to sing, but the black hole of addiction gradually stole everything he had, and when he suffered his stroke, it seemed like the end of the road.

A voice is silenced

“I was outside of Chicago, so they put me in a 50-bed hospital in Urbana, then flew me over to Loyola,” he said. “I stayed there a couple of weeks, then came back to Alabama.”

The stroke left him blind and unable to use his voice. Gradually, his eyesight came back, but his vocal cords were still afflicted a year later, even after therapy.

“I went to a voice doctor at the University of Alabama, because I couldn’t sing, and I stuttered like crazy,” he said. “I got the words in my brain, but I couldn’t get them to come out of my mouth. And that’s when he told me I’d never be able to sing again.”

For a kid who grew up singing, it was a devastating blow. While it put an end to his drinking and using, it also almost cost him everything else. He accepted the doctor’s diagnosis with glum resignation, but music wasn’t through with him, he said.

“Three years after that, I heard melodies,” he said. “When I write, I write freeform, just whatever comes to my head. So I got to writing and looked down and realized what I had done. I had never written a Christian song in my life, but I wrote four or five of them.”

He took the songs to the late influential Nashville session musician and producer Blue Miller, who had worked with everyone from India Arie to Bob Seger to the Gibson/Miller Band; he would sing the songs to Miller in a froggy voice dusty with disuse, and Miller would find the chords. As he sang them, however, he began to realize something: His voice was slowly returning as well.

“I always said I was a Christian, and I got baptized when I was 8, but I didn’t live like a Christian,” he said. “That made me go to my knees and pray. I prayed that if he would ever let me sing again, I would sing for him, and that’s what I’ve done for the last seven years.”

A different kind of song

In fact, that first Celebrate Recovery meeting in Gadsden introduced him to a group of women from a halfway house in the area. He recently received an email from one of those ladies who remembered him and wanted to share with him that she was still clean and had gotten custody of her children again. He takes no credit for such accomplishments, but he feels an overwhelming sense of gratitude for the role he might have played in her journey, as well as others who have found his story inspiring.

“I don’t make any money at Celebrate Recovery, but that’s the paycheck, and you can’t put a price on that,” he said. “I just try to give them some hope. I tell them what I used to be, what I did and what I do now, and in between my testimony, I weave songs in and out. And I’ve found that over these seven years, everything becomes clearer. You remember what you did and why you did it; the feelings you were feeling; that kind of thing.”

And while music is what brought him to the stage, it’s not who he is today, he added.

“There is no music career!” he said with a laugh. “When people introduce me, I ask them to introduce me as the speaker, because it’s not about me. I let money and ego almost ruin my life. I thought money was important, but none of that means diddly squat as you get older.”

Some of his most rewarding work, he said, is carrying his ministry to halfway houses, jails and prisons, where those incarcerated or locked down sometimes have no idea of what Celebrate Recovery offers. He doesn’t preach it as an exclusive alternative to traditional 12 Step recovery; he simply tell is like it is: that it worked for him, and it can work for anybody.

“That last big concert I did, when I opened for Shania Twain and Alan Jackson, my ego was bigger than Texas when I walked off that stage,” he said. “But just a few months later, I had to ring a bell just to get somebody to help me walk down the hall to go to the bathroom. I’ve had some really big highs and some really bottom-end lows, but I love where I am now. God has always taken care of me.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories