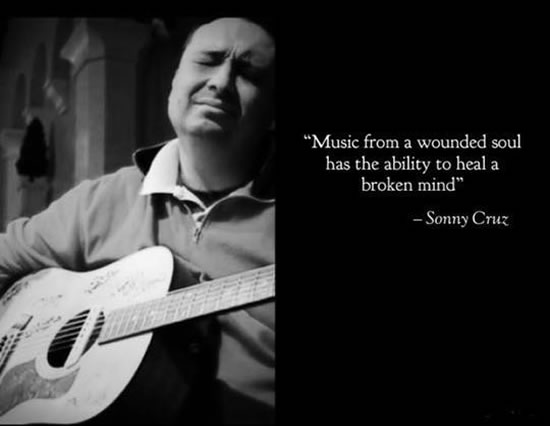

Five-time overdose survivor Sonny Cruz turns his addiction recovery into a musical mission

Five-time overdose survivor Sonny Cruz turns his addiction recovery into a musical mission

Sonny Cruz was 12 years old when he fell in love with both drugs and music, and it took a long time to unravel the two from one another.

That doesn’t mean his life is now a fairy tale. In fact, since he got clean, he’s suffered three heart attacks and has been diagnosed with an incurable heart condition, which had led to bouts of depression and even thoughts of suicide “because honestly, I just get tired of waiting for the flicker in my chest that says it’s time to go to the hospital for the last time,” he said.

Until that time comes, however, he’s determined to keep fighting — for his own life, and for the lives of others who may look to his journey as an example.

“I’ve vowed to spend the remaining time I have left fighting the disease of addiction with my story through music to anyone who is willing to listen,” he added. “I swallowed a lie that I had to be free and distort my mind with drugs and alcohol to make music, and I traded the best parts of my youth to do it. I am living proof that there is life after the party, but the tremendous price I had to pay for it has not been worth it.

“Addiction is slavery where you pay a master the best parts of your life and then get handed back the worst, mainly because the doorway to the party seems like a lot of fun.”

The illusion of freedom through drugs

“I went from being an only kid in one house to staying with lots of family in Indiana because my parents were tying up the move,” he said. “I got to hang out with my older cousins; they were 15 or 16, and I was 12 years old. And what do adolescent males do at 15 and 16? They drink and smoke dope, and that’s where I started.”

The memories of that time aren’t horrible; those would come later. Back then, he remembers riding around with five older boys, blasting Def Leppard on the car radio, watching them pass a joint back and forth. The allure eventually overcame any hesitance, and one time when it passed his way, he took a hit. He choked, coughed, took another and “instantly fell in love,” he said.

“Immediately after this, my cousin takes me to his house, where he had a 1980s hair band drum set, with drums and kicks and cymbals all over the room,” Cruz said. “Until that moment, I had no desire to play any kind of music, but I saw this drum kit, and I was stoned to the bone, and so I got on it and started kicking the most beautiful music I’d ever heard.

“Right then, when I got high, it locked me into a creative zone. It felt like I understood it. Everything slowed down, and I felt the music pumping through me. It was like, ‘Whoa!” From that moment, a bond kind of formed between me, my cousin, drugs and making music.”

The next few years, he used sporadically, mostly with his cousins. When he reached high school, he fell in with fellow stoners his own age, and because of his experience, he was immediately accepted.

“Suddenly, I was extremely popular, and because of my cousins, I had a connection at all times,” he said. “And that’s when I had my first drug overdose at 16.”

He discovered that huffing gasoline and smoking marijuana simultaneously led to powerful buzz, and one afternoon, he and a friend locked themselves in a car, fired up a joint and passed a 5-gallon gas can back and forth. Cruz passed out and woke up to his friend’s mom resuscitating him. It was his first negative experience with getting high, but it wasn’t his last.

'Medicine, religion and psychiatry'

His second overdose occurred when he and a buddy received 32 hits of powerful acid and decided take a couple and walk across the city. It didn’t kick in right away, however, and so he took more. An hour and a half later, it all hit at once, and Cruz became convinced, thanks to his religious upbringing, that the Rapture was taking place.

“I bolted and ran, and as I was getting home, this evil voice said, ‘You’re too late,’ and it freaked me out so much, it felt like I was going into cardiac arrest,” he said. “It was complete and utter insanity, and I got home and was pounding on the door. My dad let me in and then carried me to the hospital, where they strapped me to a gurney. It took quite a while for me to get OK with that.”

A horrific trip wasn’t enough to quell the growing hunger for chemical means to change the way that he felt, however. The third time he overdosed, he helped himself to Prolixin, a medication given to schizophrenics, that his uncle had on hand. Because it didn’t act quickly enough, he took more, and his neck began to swell up and spasm. He wound up in the emergency room in critical condition, where the effects were reversed minutes before he probably would have died, doctors told him later.

It was a frightening experience, but one all too common for many addicts who seek to change the way that they feel through any substance available, as quickly as possible. For Cruz, who hadn’t yet turned 18, it was a harbinger of things to come, but it was enough to scare him straight, at least for a little while.

“I settled down for the next few years, got married, had a baby and started going to church,” he said. “I switched addictions and became this super Christian. I started preaching and trying to heal people in the name of Jesus, and when the rubber met the road and things didn’t go my way, I went back to my old ways.

“I just didn’t have any education on my addiction. I thought I could go to altar, tell God I’m sorry, that he would take away my problems and everything would be fine. There was no work on my behalf, and it doesn’t work that way, and so I was in and out. I would get in trouble, go to church, become a super Christian, get tired of that, then go back out.”

At the end of the road

Around Sept. 11, 2001, however, everything came to an end. By that point, Cruz had been a patient in a couple of different drug and alcohol treatment centers, and Serotonin was being funded, he said, by a local meth dealer who liked their music.

“The problem was that we all got hooked on meth as a band, and our band practices would be just another reason to party,” he said. “It was like a VH1 ‘Behind the Scenes’ special, man. At one point, our manager tried to break my hand. We were just insane. We were barely out of the basement, but we thought we were the next big thing, acting like we had 5 million followers when only a couple of people had ever heard of us.”

Cruz embraced the rock star aesthetic, becoming a vagabond musician who couch-surfed and navigated around town on his skateboard. A fortuitous turn of events led to some buzz around his original song, “Wounded Nation,” however, and after a local radio station gave it some airplay, opportunities began to fall into his lap. The mayor invited Serotonin to play a Sept. 11 fundraiser, and Notre Dame asked if he might be interested in playing before one of the school’s football games.

However, he was picked up at a local roadblock, and while in the St. Joseph County Jail, his name matched that of an individual on the terrorist watch list that was set up immediately in the wake of Sept. 11. Even though it was eventually straightened out, he blamed his arrest for the Notre Dame deal falling through, and he went into a downward spiral of self-sabotage that cost him the band, he said.

“We thought we were about to go rule the world and sign record deals, and that was never the case, but in our brains, it was,” he said. “There was tension all through the band because we were staying up for weeks at a time partying, then coming down. I remember we were packing up to go to a gig, and the guitar player got so mad at me he threw the drumset at me, so I drove down and did the gig myself. Shortly after that, things broke down.”

A new way to live

“I was falling further into the abyss, until the shadows start talking to me out of the wall, and I just thought, ‘I’m gonna go ahead and end it,’” he said. “I grabbed this purple eyeliner that was laying around, went into the back room and started scratching my last words to the world on a piece of paper.”

The words took the form of a poem that he stands today as a stark reminder of where he once was — “I’m Stuck” — and as he read them to himself, he was jolted back to reality. Death, he decided, wasn’t what he wanted after all. He called his mother, and by this point, his parents had found a drug rehab for him in Indianapolis.

“For the first time, I was cool with it,” he said. “I had been maybe twice before, but those were just in-and-out, inpatient and outpatient settings with group therapy, but I was 17 and in there with a bunch of older folks. These old stoners and burnouts kept telling me, ‘Look, dude, this is what’s going to happen to you,’ and I just couldn’t relate.

“This time, I got eight hours a day of education and would go back to a support living facility with three other roommates. They put us in an apartment and taught us how to be a family. They made us go to meetings, and that’s what we would do for fun — we would jump in the (van) and hit meetings all over Indianapolis. More than anything, I started listening and started to understand: Maybe I do have a problem.”

In recovery, he found his tribe — addicts and alcoholics like him who used despite the legal, financial and physical consequences, who destroyed careers and opportunities, who were unable to stop on their own. He also learned how to have fun in recovery, but eventually, he had to return home. Back in Elkhart, he couldn’t find a home group of recovering people that he connected with, and his recovery was on a precarious precipice when he wound up on the doorstep of his older cousin’s house — the same one who had introduced him to weed as a 12-year-old.

“I was committed to using, but my cousin was hem-hawing around and wouldn’t let me in, and he said, ‘I’ve gotta go to this meeting,’” Cruz said. “I said, ‘What meeting?’ Unbeknownst to me, he had gotten in trouble with the law and had to go to (recovery) meetings, and I was like, ‘Dude, can I go with you?’ So we hit meetings together, and now one of my cousins is in recovery with me. For the next year and a half, we went to meetings pretty solid, and a couple of other cousins started getting sober as well. It was awesome.”

It works because he's worked it

Over time, his life started to change. While walking downtown, he stopped in the municipal building, where he was recognized for his “Wounded Nation” songwriting. One thing led to another, and Cruz went from volunteering for the city to being named lieutenant of emergency management services, during which time he helped coordinate relief for victims of Hurricane Katrina.

He started going back to church as well, eventually throwing himself back into religion with a renewed passion. The 12 Steps, he pointed out, helped repair his relationship with God, and through sober eyes, he saw spirituality through a more forgiving and inclusive lens.

“Over the next 14 years, I became a Sunday School teacher, and I would go to work,” he said. “I became a model citizen, and I’ve been able to do that because I’ve worked on my issues, and (recovery) taught me that. That’s all the Steps are — repentance, and learning how to empty out so you can turn it over to God. I was grateful, and where do I express that gratitude? In church.”

He started writing songs again, and for the past 16 years, he’s built a body of work that will become an album titled “My Toxic Life,” the strength of which he hopes to tour on at recovery centers, schools and churches. He’s written one book, “Toxic Teenager,” that will be released soon, he said, and is working on another titled “Addiction, the Sadistic Fisherman.”

Six years ago, he had his first heart attack; two years after that, he had another, and then another. He’s had to apply for disability and quit his job, and even though it’s been a challenge to stay sober under such dark clouds, he hasn’t had to get high, he said.

“I’ve come a long way, and I’m grateful,” he said. “My biggest fear is that I won’t get to tell my story. My name is Sonny Cruz; I am 41 year old; a husband and a father from Elkhart, Ind. My sobriety date is April 1, 2002. I have officially have survived 5 drug overdoses. An addict’s famous last words are always, ‘That will never happen to me,’ but I’m living proof that it can. And I’m also living proof that you can get better.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories