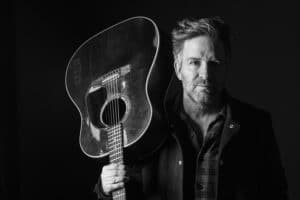

Grammy winner Mike Farris turns his addiction into a weapon for salvation

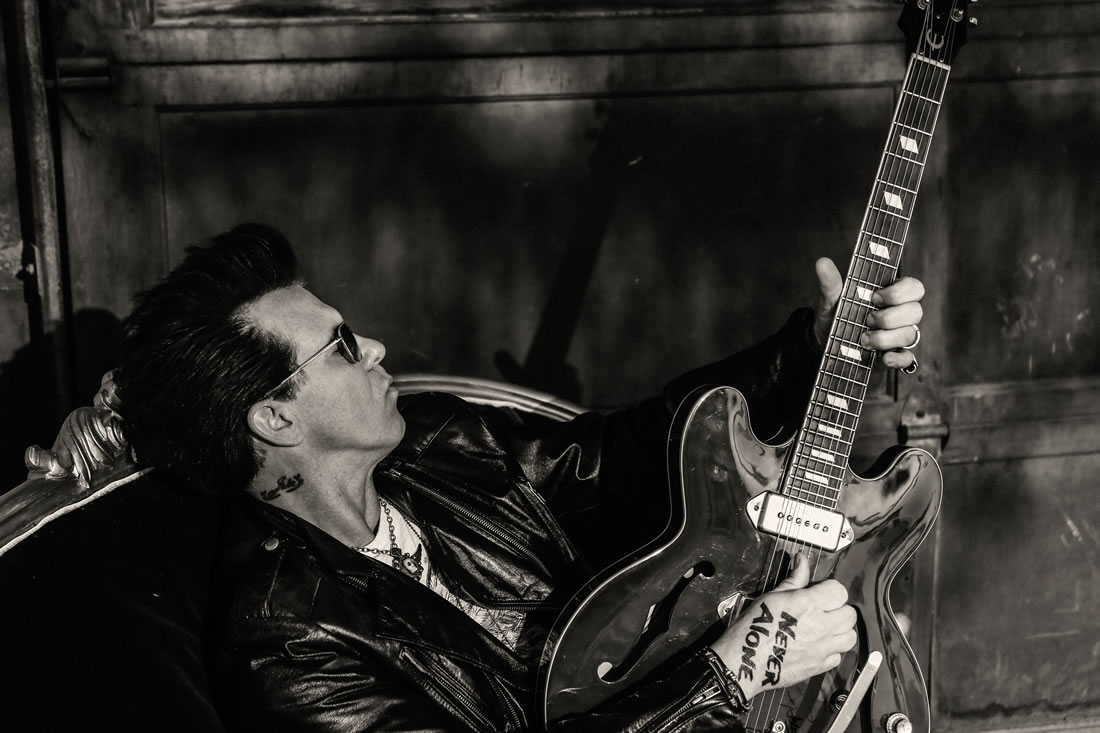

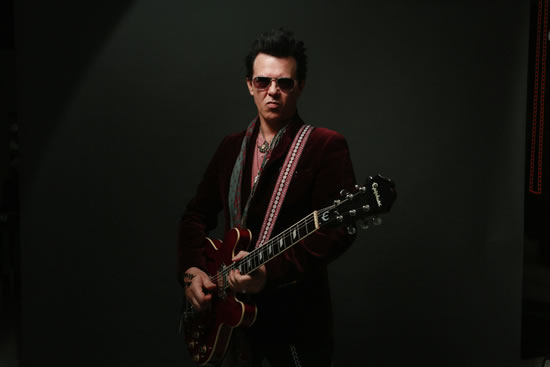

All photos courtesy of Sebastian Smith

Grammy winner Mike Farris turns his addiction into a weapon for salvation

It’s a funny thing, Mike Farris muses: The thing that damn near killed him has now become his greatest spiritual weapon.

For years, the soul rocker, Grammy winner and former frontman of the Screamin’ Cheetah Wheelies struggled with his addiction. It left him destitute and derelict, living in Tyson Park on the fringes of the University of Tennessee campus in Knoxville, not far from Cornerstone of Recovery; it followed him into a career revival that saw him reinvent his sound even as he succumbed to the siren song of opiates.

For years, the soul rocker, Grammy winner and former frontman of the Screamin’ Cheetah Wheelies struggled with his addiction. It left him destitute and derelict, living in Tyson Park on the fringes of the University of Tennessee campus in Knoxville, not far from Cornerstone of Recovery; it followed him into a career revival that saw him reinvent his sound even as he succumbed to the siren song of opiates.

These days he’s been clean and sober since 2011. He has a Grammy statue at the Nashville home he shares with his wife, Julie. And he uses his story as an inspiration to others who struggle with addiction, as well as to fans who have never touched a drug but need some reassurance that the travails of this earthly existence are worth the continued push toward the light of redemption.

“It’s amazing to me, in recovery, how the turn of events work out,” Farris told The Ties That Bind Us recently. “It’s pretty amazing that I get to use this now as a weapon against things that are trying to kill people, whether it’s drugs or whatever it is. It’s just … so insane to me.”

He pauses, clearly emotional on the other end of the phone, choking back literal tears of gratitude for the life he has today.

“Just thinking about it now, it’s a little overwhelming,” he said. “From where I’ve been, it’s just been a crazy, crazy journey.”

A cure for pain

For as long as he can remember, Farris has carried a bag of spiritual stones that have pulled him toward the abyss. As a child, he threw himself into athletics, which proved to be an effective outlet to cope with those maladies and his parents’ divorce, he said.

“I came from a broken home, and broken homes create broken people, almost 100 percent of the time, and so I was one of those kids,” he said. “But I had the gift of athleticism, so I took all of my energies and poured it into that, and that’s how I was venting my frustration, my sadness, my rage. All those things were being funneled into sports, and that was all fine and good until I had a back injury in football, and suddenly that went away.

“I didn’t have that outlet to vent those things and to focus my mind and energy on, and as soon as that went down, the opportunity for drugs and alcohol came right into my world.”

Once the seal was broken, he discovered that mind- and mood-altering substances also helped him become more extroverted. As a shy kid, he was never comfortable in his own skin, but drugs and alcohol gave him a certain exuberance that would serve him well on stage later on in life. The troubling thoughts that ran on a constant mental loop slowed, and he was able to “be a loudmouth,” he said.

“It was a cure-all in a lot of ways, and it was a great comforter for me at the time, but of course the story always ends the same, where that thing that was comforting you turns on you,” he said. “It’s a nasty trick, because it turns around and eventually ends up trying to kill you. I used to tell people all the time: The enemy’s tools are sharp and effective. That’s the way drugs are, that alcohol is: They make life so much better, but you’re just changing the channel for a moment on reality to escape it, and you wake up, of course, the next day, and it’s compounded.”

The downward spiral

When he was 20 years old, he overdosed in Knoxville, where he had been living for roughly four years. He was hospitalized at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, and after being discharged, he wound up homeless in Tyson Park, near the UT campus. That was one of his first moments of clarity, he said.

When he was 20 years old, he overdosed in Knoxville, where he had been living for roughly four years. He was hospitalized at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, and after being discharged, he wound up homeless in Tyson Park, near the UT campus. That was one of his first moments of clarity, he said.

“It’s the realization that this is not only not working, but it’s really dangerous, and it had almost cost me my life,” he said. “I didn’t realize it at the moment, but what I was really missing in my life were the basic tools to cope. Those weren’t in my bag, and when you come back around every now and then, you realize, ‘My goodness, I’m back in this vicious circle.’”

He managed to pull his life together enough to found the Screamin’ Cheetah Wheelies, which signed to Atlantic Records in 1993; over the course of the next five years, the band would release a handful of albums, including their self-titled debut, which included the modest hit "Shakin' the Blues." To this day, the Nashville-based five-piece is still considered a boogie-rock bridge between classic rock of the 1980s and jam-rock of the 1990s, and the band's music has found its way onto various soundtracks over the years.

The group toured with such acts as Sheryl Crow, the Dave Matthews Band, ZZ Top and the Allman Brothers Band, but Farris struggled with drugs and alcohol throughout the band's tenure.

“I know I didn’t do my part, and I’m 100 percent positive that my drug use was hugely responsible for that band coming up short and not having more success than it did,” he said. “I’m sure it took lots of opportunities away from us, because I wasn’t focused on my craft; all I cared about was getting high. I wasn’t working on songs, and I wasn’t working on learning how to sing and be the best I could be. I was totally preoccupied, 100 percent, with drugs, and when you’re that distracted in life, man, it waits for nobody. It will run you over.”

Even as he fronted Double Trouble, the rhythm section of late guitar legend Stevie Ray Vaughan's band, he struggled to find himself, he added. The first big turning point in his battle with addiction took place in 2005, during a Christmas trip from New York to Nashville.

A recovery journey begins

During his visit, a death in the family occurred, and relatives asked him to sing at the funeral. Standing in the cemetery at 1 in the afternoon, drunk, he stared around at the barren trees and the gray skies and saw in them a metaphor for his broken life, he said. He turned to his father, with whom his relationship had been strained, and began to weep.

During his visit, a death in the family occurred, and relatives asked him to sing at the funeral. Standing in the cemetery at 1 in the afternoon, drunk, he stared around at the barren trees and the gray skies and saw in them a metaphor for his broken life, he said. He turned to his father, with whom his relationship had been strained, and began to weep.

“I wanted to know, ‘Why am I a wreck? Why am I this way?’ I had always heard that the sins of the father would be passed on, so I asked: ‘Dad, did you ever have any issues with drugs?’” Farris said. “He just shrugged me off and wouldn’t talk to me about it, so I said forget it and went back to the car. My wife asked what that was all about, and I told her nothing, and I remember looking in my rearview mirror and seeing my dad, getting ready to go back to the world.

“And I thought to myself, ‘He doesn’t have any family anymore.’ I was determined, was dead-set in that moment, that I was never going to be that man. I remember thinking, ‘This ends today,’ and I went home that night and told my mom, for the first time out of my lips, ‘You know what? I’m a drug addict. I’m an alcoholic.’ And saying that, for the first time, was like a friggin’ exorcism. I kid you not: It was so tough to say that, but with those words, I was off and running.

“My journey had officially begun to get back square, to get clean and sober and get out of this life I was living,” he added.

He had always been a faithful man; raised in church, he had turned, off and on, to God over the years and had found grace from his struggles. This time, Farris was ready for something more — redemption. As the fog lifted, he turned his attention to the music he had been writing over the years. Filled with the majesty of old-school soul and R&B, the songs had a gospel sound to them that Farris remembers well from his childhood. The result was “Salvation in Lights,” a holy-rolling, piano-pounding, booming-voice of an album that’s pure Holy Ghost-fueled energy.

It’s a praise-and-worship album, a mix of Farris’ original compositions and old standards, and it was incendiary in its passion. With a voice that sounds elated and triumphant, Farris sang his heart out and never let the listener doubt for a minute to whom he’s giving all of the credit.

Despite the career revival and the spiritual solace he found in a new sound, however, addiction wasn’t quite done with him yet.

There and back again

“I didn’t go to rehab at first; I didn’t do AA or NA or any of those things,” he said. “I did it through the help of my wife, Julie, and my friends, and of course what happened was that I relapsed.”

“I didn’t go to rehab at first; I didn’t do AA or NA or any of those things,” he said. “I did it through the help of my wife, Julie, and my friends, and of course what happened was that I relapsed.”

Back surgery led to opiates, which kick started his dormant habit. His opiates phase lasted several years, he said, during which time he manipulated his way into more prescriptions and maintained a secret life apart from the Mike Farris everyone thought they knew. The center couldn’t hold, however.

“I was actually on my way to get pills, but living in my secret little world, getting high, started to wear on me,” he said. “The voices in my head were saying, ‘We should keep this from Julie. She wouldn’t understand. She doesn’t get it.’ But I pulled into the doctor’s office and called her and said, ‘You know what?’ and I confessed it all. I told her everything I had been up to and said, ‘I’m gonna go in here, get these drugs, come home and give them to you. I want you to help me get off these things.’

“And the beautiful thing about my wife was that she said, ‘Okay. Come home. Let’s do that, and we’ll get through this. But we’re going to do something different this time. This time, we’re going to get down to why we keep coming back to this point; why you’re so self-destructive; what made you this way. We’re going to do some hard work.’ And I said OK, and we jumped into it.”

He attended an Intensive Outpatient Program, started going to recovery meetings and began unpacking a lifetime of pain. Since 2011, he’s maintained the vigilance required to keep his addiction at bay, and he’s reached a point where he’s able to love himself, he said.

“We don’t see the beauty in ourselves, and we beat ourselves up,” he said. “This far down the road, I’m realizing that getting the drugs out of your system is just the beginning. It’s the journey after that, and it takes a while to escape that insanity and start seeing things with clarity, to start seeing things a different way and start realizing that this is an ongoing condition I’m going to have to manage. It’s not, ‘I’ve gone through rehab and I’m ready to go!’ If you don’t manage it and keep it in the box, it will escape, and it will try to destroy your life again.”

A spiritual paycheck

There’s a recovery cliché that applies to Farris’ story: “The work is hard, but the pay is worth it.” It’s a mantra that he feels in his soul today, and he expresses it through the music he’s continued to make: “Shine for All the People,” which won the 2015 Grammy Award for Best Roots Gospel Album, and “Silver & Stone,” released earlier this year. The Grammy Award alone was a material blessing beyond measure, he said, but it only served to encourage him to continue to nurture his spiritual gifts.

“I just saw it as a moment where God was giving me a chance to go to the mountaintop and just take a look and take in the view, but then realize that, ‘We’ve gotta get back to the valley, because there’s more work to do,’” he said. “That was really what it was all about for me: a moment to stand and enjoy it, but also to realize, that was just a moment, that we’ve got to get back to the valley and get back to work.”

It’s not always easy work, and when he faces studio deadlines and tour demands and label negotiations all on top of maintaining a healthy relationship with his family and a commitment to his recovery, it can be downright grueling.

But the pay is indeed worth it, he added.

“Honestly, man, that’s a beautiful, beautiful gift, just learning to work on becoming a better human being,” he said. “What better, what more noble, work can a person do with their lives? I’m a survivor, but my job, the greatest job, is to share that with other people and give them courage to do the same.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories