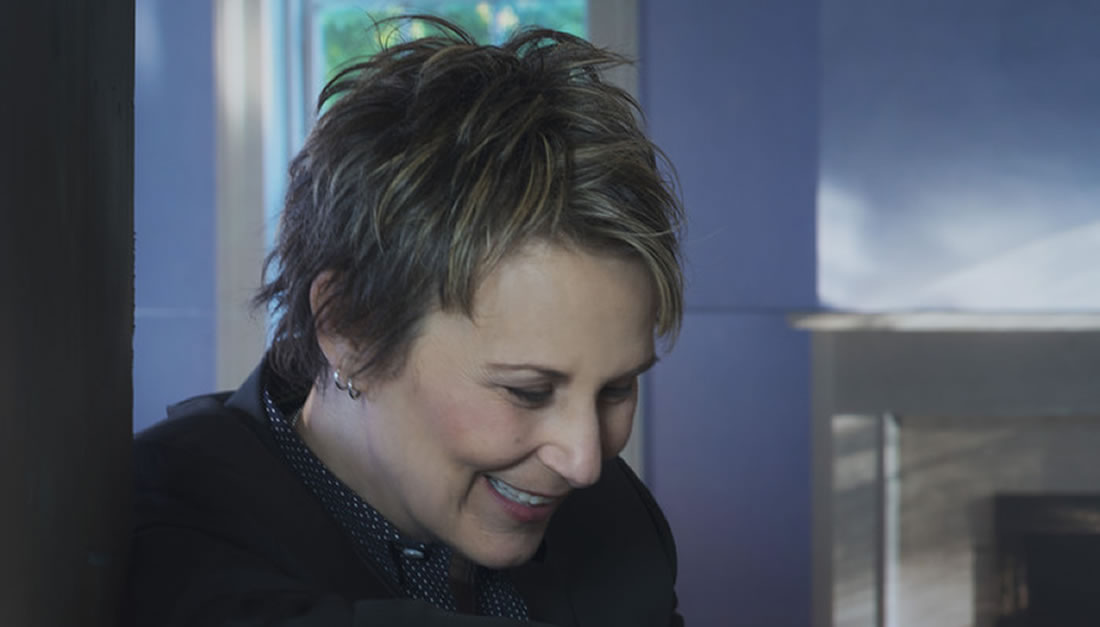

Mary Gauthier: ‘I’m so glad I’ve remained willing to do what it takes’

Mary Gauthier: 'I'm so glad I've remained willing to do what it takes'

For a girl growing up in Louisiana with a gaping wound where her heart should have been, alcohol was a balm for the soul.

Abandoned by her mother as an infant, Mary Gauthier — a critically acclaimed songwriter and neo-folk artist whose work rings with the poignancy and pain of hard truths, hard times and hard beauty — can’t remember the first time she discovered its warm embrace, but she remembers what it did for that deep ache, she told The Ties That Bind Us recently.

“I remember being drawn to it in a way that there was no turning back,” she said. “From the get-go, it was, ‘You’re not going to stop me; I’m going to do this,’ because the sensation was one of not feeling like I was in pain for a little while. That’s a sure sign of alcoholism, when you get the sensation of liberation from pain instead of taking the edge off of a little bit of social unease.

“For me, it was like Dilaudid for someone with cancer. I felt less pain, and there was no way you were going to stop me from not feeling pain. I was like a moth to flame from the get-go.”

From the filth to the fire

“I wanted to get away — from my family, from high school, because I didn’t want to be in high school. I didn’t want to be around a place I did not fit in at all,” she said. “I wanted to get away, so alcohol was my great escape. I quit high school, because that was just misery for me. On top of being an addict and an alcoholic, I was a gay kid, and back then, that just didn’t fly. Back then, gay kids were taking their own lives. It was horrible, and I just wanted to get away.”

And so she kept running, drinking and using throughout most of her 20s until she finally got sober in 1990, at the age of 27. By that point, she had enrolled at Louisiana State University as a philosophy major, dropping out her senior year and moving to New England to attend the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts in Boston. She drew on her Louisiana roots to open a Cajun restaurant, the Dixie Kitchen, but she was arrested for drunk driving on opening night — July 12, 1990. That, she said, was her moment of clarity.

“The big picture for me was handcuffs and being in a cell alone, in isolation, for I don’t know how many days,” she said. “That suffering, in that cell with me and my brain, was enough to convince me, ‘You’ve gotta do something here.’ I had a moment in that jail cell where I left my body and saw myself. It was just for a millisecond, but I left my body and looked down at what I saw — terror, bewilderment, frustration and despair. So I said the words, ‘Help me,’ and I think my life started to turn around that day.

“I didn’t know it of course, but in retrospect, I think that was the beginning of willingness. The next morning, I went in front of the judge, and he sentenced me to a 12 Step program. I had gone before, but I was just visiting — mostly scanning the room for girls. The second time, I was still scanning for girls, but I needed to be there.”

Those magnificent rooms

“I don’t think we talk about it nearly enough, how important the group is,” she said. “I think the fellowship is really important to people like me who tend to be isolated. I still tend to be socially awkward; I’m what I like to call an introverted extrovert. I’m great in front of a crowd or in a group, but one on one, I start to get anxious. The way the fellowship is set up, there is no leadership, and no one’s in charge, so you have to learn to work together.

“The fellowship itself is such a big part of why I still go to meetings. I just want to be around my kind. I like my fellow drunks; I love watching them come in and get clean and transform. I like to say it’s the best show in town, because they start to realize their potential and become useful. They become stable and solid and happy, and where else do you see that, except in the rooms of recovery?”

When she got sober, she said, her life truly began. She went back to running the Dixie Kitchen, but she was hungry for something more.

“As part owner, I had the challenge of running the business and the joy of being able to serve people food and to feel the satisfaction of them enjoying it, but I needed to go deeper than that,” she said. “I found through song and songwriter that something that went further, and in retrospect, I think it was important for me to find music and find something that brought purpose to my work.”

The restaurant was located practically next door to Boston’s acclaimed Berklee School of Music, and by proxy, she found herself a part of that community, serving them food and listening to their stories and soaking up their culture. She began writing songs, and found the willingness to play them at open mic nights around town, and in so doing, she found another support group — the struggling artists of her town in addition to her fellow recovering alcoholics and addicts.

Her first album, 1997’s “Dixie Kitchen,” was named after her restaurant, and shortly after its release, her muse began to demand her full attention. She sold her stake in the business to finance her second album, “Drag Queens in Limousines.” She moved to Nashville in 2001, and her 2002 album, “Filth and Fire,” got her noticed by the major labels (and was named the “Best Indy CD of the Year” by New York Times music critic Jon Pareles). After 2005’s “Mercy Now” — which wound up on an overwhelming number of year-end best-of lists — she was suddenly hailed as a brilliant new voice in Americana songwriting. Other records followed, and “Rifles and Rosary Beads” — released earlier this year — is her latest effort.

It’s an outgrowth of her work with the nonprofit organization SongwritingWith:Soldiers and features 11 songs all co-written with and for wounded veterans. It’s a visceral collection of pain and beauty, and for Gauthier, it’s an act of service that’s also an instrumental part of her sobriety.

“For me, personally, this is what I imagined long-term sobriety might feel like — the ability to work with a lot of people peacefully and move something forward that’s useful to others,” she said. “I’m not a soldier, and I don’t have any experience with war, but I’m happy to help others tell their stories and to use my talents to help others. It’s a blessing, because in recovery, that’s where we find our joy — making ourselves smaller so that we can be useful to others.”

The 'amazing ride' continues

And while she’s always walked comfortably alongside songs that cast long shadows, she’s trying something new for her next project: love songs, she added with a laugh.

“I’m in a new relationship, and I’ve not really done that before, but it’s a strange thing when soldiers — trained killers, really — are able to teach me about peace and love,” she said. “That’s how it’s been. I’ve learned so much from them, and with these new songs, I’ve applied some of what I’ve learned. I’m just grateful that HP (Higher Power) sees fit to put somebody in my life, and I’m trying to capture these early days of love in song.”

But really, her entire catalog is a love letter: The “love, empathy and compassion of my fellow travelers” in the rooms, she said, have given her a life beyond anything she could have imagined at the outset, and the past 28 years have given her the inner peace she so long sought as a girl and a young woman who thought she’d find it in a bottle.

“It’s definitely an amazing ride; it goes way slower than you think it should, but it’s not a race, because there’s no destination, of course,” she said. “If you just stay on the journey, the scenery changes. I’m so glad that I’ve remained willing to do what it takes to stay in recovery and to stay connected to other people in recovery, and to really understand that the whole thing is hung up on willingness.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories