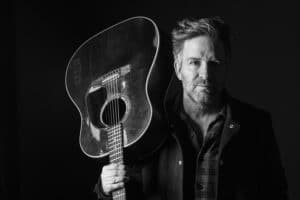

On the cusp of a new album, singer-songwriter Michael McDermott celebrates authenticity

Courtesy of Tony Piccirillo

On the cusp of a new album, singer-songwriter Michael McDermott celebrates the authenticity of a sober mind and a grateful heart

Before the modest stardom and the MTV fame, and even before addiction took hold of his life and nearly wrecked it, singer-songwriter Michael McDermott used to stare up at the heavens over Michigan and feel insignificant.

“We were only trying to feel like we belonged to something,” he said. “As a kid, I would look up there and think about how there were galaxies beyond what I was looking at, and other galaxies beyond that, and others beyond that, and I would get myself into a frenzy. I was so terrified, and I felt smaller and smaller, and my knee-jerk tendency was to isolate.

“And the isolation kept happening throughout my life. I would be in the crack house, or shooting up, and I would get smaller and smaller still, and I would think, ‘I don’t want to be with these people.’ I never felt like I belonged.”

Recovery, however, has changed his perspective. Today, he meditates regularly and prays for a connection, and he’s found it through a program that’s given him a tribe, as well as through music that’s given him a purpose. He’ll release a new album — “Orphans,” out this week — and he’s made peace with the existential crisis that seemed to plague him all of his life.

It’s all about balance at this stage of life, he added: knowing his place, and being OK with it. That acceptance allows his music to ring with the sort of genuine emotion that earned him admiration from author Stephen King, among others, as well as from the modest collection of fans who show up to hear an artist who’s unafraid to put his true self on display through song.

Keith Richards dreams

“There was a band there in town, and I used to watch them rehearse, and that’s how it all started musically for me,” he said. “That’s kind of when music took hold, and obviously it changed its meaning over the years. It’s a snake charmer of sorts. It’s like an elixir that allows you to bring the things you struggle with into the light.”

It take more than writing and singing about them to address those issues, however — that’s a lesson recovery has taught him. Sharing them with the world is one thing, but doing something about them is another challenge altogether.

“I’ve found, in my new life, that when I do transcendental meditation, it’s in the silence where you really have to confront those things,” he said. “Music heals, and I think it unlocks the areas of your life where you’re struggling, but I think the actual confrontation is one in a different area.”

It would be several years later before such lightbulb moments would be realized, however. Those first couple of summers, the boys in the band taught their young hanger-on a chord or two, and during the school year, he’d return to Chicago and practice. The next summer, he was invited to be a part, and eventually he was drafted to sing.

“I never wanted to be the singer; I just wanted to be Keith Richards!” he said with a laugh. “And I achieved some of that, but not quite the whole way.”

'A Wall' goes up

“620 W. Surf” was released in 1991 on the Giant/Reprise label, and one single, “A Wall I Must Climb,” got some traction: It peaked at No. 34 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock Tracks chart, and the video got some MTV airplay. McDermott found a modest amount of fame as a buzz band, but as quickly as his fame took off, it was just as soon done.

“Everything was aligned for success but didn’t happen, and shortly thereafter, I was washed up by the time I was 23,” he said. “That was a bitter pill, to go from that to having to worry about how many people in Des Moines are buying your record. When that happens, you’re (screwed).”

Around the same time, his addiction began to find its sea legs. He was never a big drinker or partier, choosing instead to focus on his career, but a drunken night here and a line of coke there began to seem more appealing as his mainstream career lost traction. As an avid reader, he began to blur the lines between the rebelliousness in the works of Arthur Rimbaud, William Blake, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway and his own life, he said.

“The life of the rogue, the rational disorder of the senses that Rimbaud talked about — I believed that, and I lived it,” he said.

It was a slow descent, and during that time, he continued to make music that caught some high-profile attention, even if it didn’t chart like his earlier works. In 1996, he struck up a friendship with the writer Stephen King, who had received a copy of McDermott’s sophomore album, “Gethsemane,” as a Father’s Day gift from one of his sons.

“My first listen to ‘Gethsemane’ is one of the great events of my life as a rock music fan,” King wrote in the liner notes for McDermott’s 1996 self-titled record, on which he also contributed a guitar part. “Michael McDermott's music, like Springsteen's and Van Morrison's, helped me to find a part of myself that wasn't lost, as I had feared, but only misplaced.”

A King reaches out

In McDermott, King saw something of a kindred spirit. The author got clean and sober in the late 1980s, and on an occasional trip to Memphis, where McDermott was living at the time, he saw a younger version of himself.

“He caught wind that I was burning it pretty hard, and he wrote me this eight-page typed letter of how he got clean and his sobriety,” McDermott said. “I read it and wept, because some of the things he wrote in the letter were so beautiful. I was curious about how it worked, and he had all the great answers.”

McDermott wasn’t ready to do something different, but the letter was sacred. He carried it with him and would bring it out in whatever drug dens he found himself to impress his using buddies, he said.

“In those houses, there’s always a lot of talk about stopping, and when I’d bring it out, they’d all go, ‘Whoa!’” McDermott said. “There’s more talk about God in a crack house than any church I’ve been to.”

Other times, he’d take it out during the dark hours of the night, read it and weep. It seemed like an unattainable dream, and as time went by, he squirreled it away, eventually discovering it years later in a scrapbook his mother had put together. He read it once again and took note of the date: Feb. 23, 1996.

“I just thought, what kind of idiot takes 17 years to get it together?” he said with a laugh. “He knew I was in trouble.”

McDermott did his best to get clean on his own. He gave an outpatient program a half-hearted effort; he established sobriety deadlines that were always broken; he skirted a number of potential legal entanglements that could have led to hard time.

“I was worried, but not terribly,” he said. “There were just a lot of burnt bridges, man.”

The end of the road

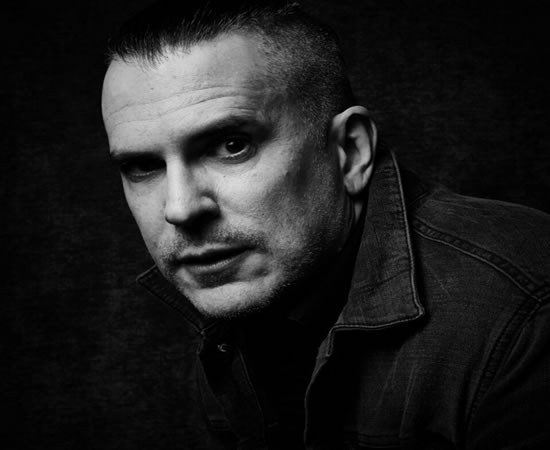

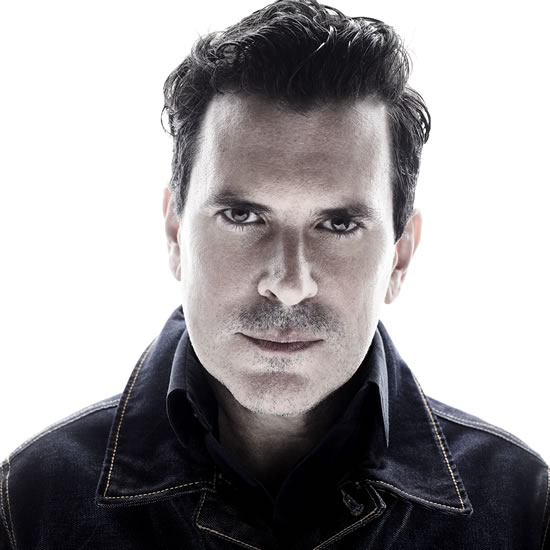

Michael McDermott (left) and his wife, singer-songwriter Heather Horton. (Photo courtesy of Jeremy McCarthy)

Including on the homefront, and that’s where his using came to an end. By that point, he was preparing to die, going so far as to tell his wife how much she’d miss him when he was gone. His daughter stared warily across the dinner table, not recognizing, the sallow, yellow-skinned guy who regularly passed out sitting up. One morning, his wife gave him an ultimatum: The hospital or a meeting. His choice.

“The idea of going to a hospital wasn’t pleasant, so I made the call,” he said. “From then on, I thought I was doing it for her.”

He even went so far as to plan a relapse: He had a string of dates coming up in Germany, and there, where nobody knew him or would keep an eye on him, he could go nuts, he thought.

“But I got there and thought, ‘Other people might not know, but I’ll know, dude. I’m gonna know,’” he said. “That’s the first time I took agency and governed over my own decisions as opposed to being a slave to them. And in that moment, I realized, I’m that guy.”

“That guy” began a long walk back into the light, one that’s still taking place but has gotten easier to tread. It was difficult at first, especially on the ground in Germany where the streets were awash in beer, but it set the stage for what would be a triumph of willingness during that first year, he said.

“It’s the mental elements of being a drunk and an addict that I fight with, and that first year was difficult,” McDermott said. “The first thing you think about is, how is this going to affect the way I write? The way I perceive things? The way I perform? Learning to have a conversation with people you weren’t familiar with and looking them in the eye.

“There’s a great quote by Hawthorne — ‘No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true.’ You’re one person at the office, another at the bar, another with your wife and kid, because there are all these different masks you wear. And that was the thing — I had to burn those guys down.”

New paths taken

His first post-sobriety record, “Willow Springs,” was released in 2016, but his songwriting hasn’t changed all that much. For one thing, he said, he never wrote while he was using, because he revered the craft too much. For another, he’s always been reticent to talk about his process, he added.

“I think it’s a jinx, of sorts, and I just do my job and put my heart into it,” he said. “All along, I never thought that anybody would really like it, and even though people say, ‘Don’t you know you made a great record?,’ it still disappears in three weeks.”

What has changed is his ability to tell a story on stage completely sober. There’s a tenderness to the songs on “Orphans” that speaks to the nuances of a sober mind: the intricacies of life viewed through a lens of clarity that wasn’t always present, and the belief that no matter the storms, there’s always dawn on the other side of that long night.

“When people post pictures of old shows where I was geeked out of my mind, I cringe,” he said. “I was the guy who would spend three days in a crack house nailing comforters over the windows because the light was the enemy, and I can see that in my eyes in those photos.

“I hated that guy. Now, a lot of the ego is gone. I still have some of that, but I know where I am now, and I know those delusions of grandeur are far fewer. It’s funny, because it is a surrender. The word surrender sounds like a weak word, but it’s not. It’s a word of strength to me.”

There are still moments where his old thinking attempts to reassert itself, those fleeting thoughts that a drink or a line might anesthetize the inherent discomfort that so many addicts and alcoholics feel when they’re not wearing that chemical suit of armor to protect their vulnerable selves.

“It’s that feeling of being a fraud,” he said. “I always felt undeserving of any success, and that being sober, that avatar would be removed and everyone would see me for the complete and utter fraud that I thought I was.

“Today, it’s addition by subtraction for me — staying out of the way of myself and not being so self-aware. We’re our own worst enemies sometimes. If anything, I hope what I’m doing today is more authentic.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories