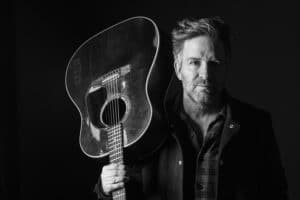

Singer-songwriter David Easterling: ‘We all support one another on this journey’

Singer-songwriter David Easterling: 'We all support one another on this journey'

In the family home, an old intercom system, popular in the ’60s and ’70s, would broadcast to every room, and from the third grade on, Easterling told The Ties That Bind Us recently, he would set it to a favorite radio station every morning as he got ready for school.

“I remember listening to all sorts of songs, but by 13, I was listening to more folk music,” he said. “My brother was eight years older, and my sister was 10 years older, so they introduced me to a lot of Peter, Paul and Mary; Bob Dylan; The Eagles; and even The Beatles — folks that were actually saying something in their music that was meaningful to me.

“But I also remember hearing songs on the radio a lot and thinking, ‘That’s not a very good song. I could probably write something better.’ And I guess I challenged myself to do it, but it took me a long time, probably, to write something better.”

These days, he’s approaching somewhere between 400 and 500 original songs, many of them tempered by spiritual themes that have long been a part of his life but have only grown more poignant the longer he’s been in recovery. Recovery, in fact, has given him as much as music ever did, and when the two are applied in tandem, the results are life-affirming for both Easterling and the audiences for whom he plays.

“Recovery was more than just getting sober,” he said. “It was an opportunity to change a whole lot of things in my life.”

Discovery of a calling

“I lived in his shadow for a long time,” he said. “He could do everything better than me, but the reality was that he could do most things better than everybody. He was very popular, he was the football player, he was the homecoming king. But I could do this music thing, so when I got this guitar, I would play all the time.”

The first song he ever wrote was titled “Just For Fun,” and while he doesn’t remember any specific lyrics, in hindsight, believes it was prescient.

“Technically, it was a song about getting out of a codependent relationship so the person could thrive in life and do well,” he said. “It wasn’t a great song, but I think that’s probably what it was about, but I don’t know that I knew what that was back then.”

Drugs and alcohol weren’t a part of his upbringing at all, but he was always driven to succeed. As he got older, he carved out a career as a writer and musician, but in the 1990s, he found success from a most unexpected place: a card game.

Redemption was based on a similarly popular concept, Magic: The Gathering, but involved Biblical characters, places, objects and concepts. The object is for the “Heroes” of the game to rescue five “Lost Souls” by defeating an opponent’s “Evil Characters,” and it was first introduced in 1995 by Cactus Game Design. Easterling helped to develop the game in the early years, served as the game’s rules arbiter for several years and wrote the influential “Redemption Players Guide,” published in 1997.

“I took it to Christian music festivals and national youth conventions all over the country, and that’s how I did some concerts along the way,” he said.

He wrote for the United Methodist Publishing House for six years, wrote three books, edited three additional books and contributed material to roughly 20 more; he penned around 100 articles in various magazines, and as a solo artist, World Vision sponsored him. Life, it seemed, was good.

Addiction, however, had other plans.

A tumble into the abyss

David Easterling (right) with his wife, Laurie.

“I had all of these different avenues of financial support that all worked together as a really nice full-time job, and I had a lot of time off, also, in which I wrote a lot of songs,” he said. “I was so busy I always had to have an assistant, someone to travel with me, because I was going out for three weeks at a time, setting up merchandise booths and that kind of thing.

“One of the last assistants I had, I didn’t choose very wisely, because my parents died, then I lost one of the financial streams and a couple of other things happened, and it kind of felt like the world was caving in around me. She said, ‘Here, try this; it’ll help,’ and before I knew it, I was hooked in that active addiction downward spiral for a couple of years.”

Easterling’s bottom wasn’t as low as other musicians who have found their way to recovery, but it didn’t have to be. Addiction isn’t about a specific substance, according to 12 Step literature, and recovery programs aren’t “interested in what or how much you used or who your connections were, what you have done in the past, how much or how little you have.” The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop using, and by those standards, Easterling qualified.

“About two years in, I just could not stop on my own,” he said. “If I could have, I would have. At the time, I really didn’t know anything about recovery; I didn’t know anything about meetings and all that kind of stuff. But there have been about half a dozen times in my life where I have heard the voice or felt the hand or direction of God in a very sort of real way, and this was one of them.

“Right about that time, I felt a hand on my shoulder, and I heard a voice that said, ‘Enough? Enough.’ It was miraculous. Now, I was hardheaded enough that it took a few more days to ask for help, but I sat down with my wife, Laurie, and told her what was going on, and she said, ‘We’ll go to Cokesbury.’”

At Cokesbury United Methodist Church in Knoxville, Easterling was introduced to Celebrate Recovery, the Biblically based addiction recovery program that grew out of Saddleback Church in California; after consultation with a friend of his wife’s who happened to be a drug and alcohol counselor, Easterling called Cornerstone of Recovery. A few days later, he became a part of the Intensive Outpatient Program.

That was the start of his recovery journey, almost 11 years ago.

“I don’t have stories of years and years of struggle, with everybody in life being mad at me, with divorce,” he said. “It’s just a story of backing into the quicksand, not being able to find my way out and then being humble enough to ask for help.”

A journey back into the light

“Ninety meetings in 90 days — I thought that sounded kind of impossible. How could anybody do that?” he said. “But I threw myself into it, and I did over 100. I think it was the third meeting I was ever at, and a couple of things that were said had a lasting impact on me. One was a guy who said, ‘I’m grateful for my disease.’ At the time, I thought, ‘That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard, because I didn’t want any of this kind of stuff to happen to me!’

“It took me a while to realize that it gave me an opportunity to make some really big changes in life that I wouldn’t have made otherwise. The disease wasn’t my problem; I was my problem — the way I approached life and made decisions, the way I was in relationships, all that kind of thing.”

Those big changes included weight loss surgery a year after getting clean — “The road had not been kind to me, and I did not take care of myself in that 12 years I toured,” he added. He lost more than 200 pounds, but more than they physical changes, he found a weight had been lifted from his wounded soul. He got a sponsor in the program early on, but he also found his “tribe.”

“I realized that even though there were a lot of folks in recovery that I would probably never have hung out with, it occurred to me that these were my people,” he said. “I spent a lot of time early on, and over the years, going and getting something to eat and just hanging out and talking with folks in recovery. Last week, I went to a meeting with a friend of mine who had relapsed, and I was there when he got his 30-day chip, and it was real meaningful to him. Just that kind of thing.”

After he completed the Intensive Outpatient Program at Cornerstone, he continued to attend the voluntary Aftercare meetings for an entire year, and even now, he drops by on occasion just to check in, touch base and remind newcomers that the program works. It keeps him grounded, he said, and it helps him to be a better spiritual adviser to the current crop of Cornerstone clients.

“I’ve always been in ministry for people who are hurting, but I never understood the depths of pain and hurting until I went through some of that myself,” he said. “Being a wounded healer allows me to empathize better, and it allows me to help folks out of the shadows in an easier, quicker way, because I had to learn to leave my baggage behind as well.

“I realize more quickly and clearly when I’m getting in my own way these days. It was really important for me to not try and out-think the program, to be compliant and do the things I needed to do. I had to be as consistent as possible in building new habits and new ways of thinking.”

Recovery makes the music more powerful

“I found most of those songs had some sort of answer or redemption in them, that there was some kind of a turnaround in them, and I forced that into some of my older songs, because I thought it was supposed to be there,” he said. “But what I’ve found more these days in life is that some days are tougher than others. Some days you see the answers, and some days you barely know what the questions are. So the songs I write now are more about people in a moment of time.

“I have one song called ‘The Old Me’ that’s real gritty, but in there, (the narrator) says, ‘Lord help me, keep me from the old me.’ There’s no summing up to that story that tells what door he ends up going through, and some people are uncomfortable with that. They want that resolution, but that’s not where that character is at that moment in time.”

Life, more often than not, doesn’t always have a neat resolution. Recovery isn’t about tidy endings and happily-ever-afters; sometimes, it’s just about hanging on and waiting for the storms to inevitably pass. That realization, and its application as a storytelling device in his music, lends Easterling’s songs a depth and authenticity that touches hearts and souls. It’s also allowed him to make connections with other songwriters who hunger for the genuine and recognize a kindred spirit in Easterling’s music.

“In the last three years, I’ve met other songwriters and done gigs in areas where I can stay with them,” he said. “I’ll write with them, go do a gig and just have fun and not worry about a lot. Last year, I played in Alabama, in Georgia and Tennessee, in Indiana, in Wisconsin, and that’s been a big change.

“I never really thought about traveling and playing much (after he got clean), and I thought that was all done. But then all of the sudden, I had this renaissance of writing again, and I’ve written about 140 songs in the last couple of years. About 40 of those are co-writes with writers all over the place. Laurie and I tend to write quite a lot these days as well, and I’m even writing with some country songwriters, too.”

Growing up in Eastern Kentucky, he never really fit in with the bluegrass or Appalachian music that was so prevalent in the region; his work tended to follow in the footsteps of titans like Dylan, Neil Young, Dan Fogelberg and Randy Stonehill. These days, he earns comparisons to other tunesmiths whose works are untethered to any particular genre — John Prine and John McCutcheon among them, the latter of whom puts on a songwriters gathering every summer at the Highlander Center in New Market, Tenn., that Easterling attends.

What he’s learned over the last several years is that the muse should be accommodated, whenever she pays him a visit, he added.

“When the muse calls, you have to pay attention, because it may not last,” he said. “My family knows that if I’m in the middle of something and have an idea, and I get up and go to write, that’s just what I do. I remember that first night at John’s camp, I was awake at 4 a.m., because our cat that usually sleeps in the crook of my arm wasn’t there, and I immediately started writing about that. The next morning, I looked at what I wrote, crossed out four words and realized I had a sweet little waltz about my cat.”

Songs of healing and hope

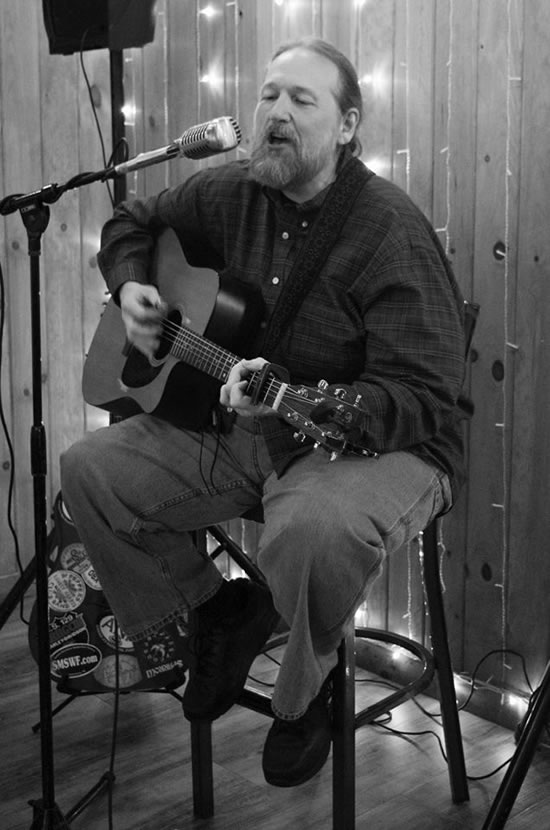

Recovery has also allowed Easterling to broaden his musical horizons. While he played in a college band, it wasn’t until he became part of the Cornerstone family that he found himself collaborating more with other musicians. At Cornerstone, he co-founded The Gathering, a monthly celebration that pulled together a number of area musicians to perform on the Cornerstone campus for members of the local recovery community and invited musicians in treatment to share their talents.

In addition, it’s not uncommon to walk through the Caldwell Center and hear Easterling playing guitar and singing in one of the spiritual groups he moderates weekly. Seven years ago, Mark Beebe, the director of Recovery Ministries at Cokesbury, was moderating night groups at Cornerstone and asked Easterling to sit in with him. The next week, Beebe couldn’t make it and asked Easterling to fill in. Shortly thereafter, Beebe turned over the spiritual advisor position for night IOP groups to Easterling.

“It’s a calling,” he said. “I’m just there part-time now; I do spiritual meetings once a week with the Young Adult Program and the Recovery Renewal Program, and then I do some one-to-one sessions when those patients decide they want to talk to me about something. I do some of the Fifth Steps with members of the Newcomer’s Program and the IOP guys; some weeks I’m not there for many hours, and some weeks I’m there quite a lot.

“It is a ministry, and it’s how my ministry calling has shifted. I try to use music to spark discussions as much as I can,” he said. “It is a calling, and I’m grateful for it, because it’s a real important part of recovery. I think the guys bond with me pretty easily. We all support one another on this journey.”

Buckle Up Baby written by David, Laurie and Dan and performed live on The Blue Plate Special by David Easterling w/ Dan Raza on July 31, 2018. Please feel free to share with your friends! 😁🎶

Posted by David Easterling on Monday, September 17, 2018

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories