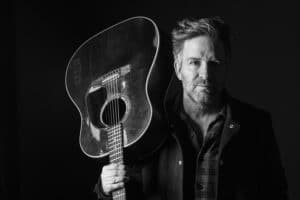

Singer-songwriter John Dennis: ‘Things got wildly better’

Singer-songwriter John Dennis: 'Things got wildly better'

As long as he lives, singer-songwriter John Dennis will never forget his last day.

That morning, he woke up, and he knew.

“What I distinctly remember is that it was my last day,” he said. “I said, ‘Today’s the day I’m going to kill myself.’ I spent the entire day drinking, taking a cold shower, drinking, taking a cold shower. I knew it was the end. And there was a guy I had gone to treatment with who had tried reaching out to me, and I texted him and said, ‘I need to talk to somebody.’

“He called, and I didn’t answer, so then he texted me: ‘Where are you?’ I was in that place of total desperation, so I sent him the address, and he showed up at my apartment. Even though I was in horrible shape, he was so welcoming that all the shame I felt dissipated. He said, ‘There’s a meeting in 20 minutes,’ but I wasn’t ready, so he said, ‘How about you go back to treatment?’

“I was so totally desperate, so bottomed out, that I recognized there was no other path, so I went and checked myself in for 30 days,” he added.

He made it back to Cumberland Heights, the Nashville-based treatment center where he wound up for the second time, with days to spare. Given the amount of alcohol he was consuming, combined with his general poor health and lack of nutrition, it’s doubtful he would have lasted another week, staff members told him.

“Once I was there, I was humbled, and I really decided I was going to do it and really listen,” he said. “I got out and lived in in a halfway house, and even though that’s not what I wanted to do, I realized that what I wanted got me to that point.”

A Day in the Life

“I was browsing through the CD section, and I came across ‘1962-1966,’ the Beatles’ early years. Part of me was searching for something, and I had heard that name, so I thought, why not check it out?” he said. “I put it in the car driving home with my parents, and with them singing along to it, I immediately fell in love. I couldn’t get enough of it. By the end of the week, I had convinced my parents to buy me an electric guitar, and I wanted to be the next George Harrison.”

He started out teaching himself to play songs like “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” and after a few months, his parents found him a guitar teacher in Freeburg, Ill. Although he loved playing electric guitar, he soon found that his talent made him more of a rhythm player, and so he gravitated toward the acoustic. An older brother gave him a list of 20 “mandatory” albums to check out, everything from the Stones to Tom Petty to Jimi Hendrix to Alice in Chains, and Dennis devoured every single one.

In the eighth grade, he started a band with a friend who played bass, and while they struggled to find members, they journey was the springboard to a cover group — the Still Montgomeries — that played the bar scene throughout his high school career.

“We did some originals, but it was mostly covers of rock and country stuff,” he said. “Now that I’m here in Nashville, the emphasis on original music is so great here, but it’s hard for me to imagine what my writing would be like if I hadn’t had to learn all that great music and spend so much time with those great records, learning the craft.”

After high school, Dennis moved to Nashville to attend Belmont University, determined to study the guitar. It was there that his world collapsed.

Carry That Weight

The plan, Dennis said, was for his girlfriend, Adrienne Glauber, to follow him to Belmont. A year younger, the two had dated for more than three years. Both loved music, and both wanted to study it. However, during his first semester at Belmont, Adrienne was killed in a car wreck.

“That totally derailed my life,” he said. “Really, up until that point, I had never experimented at all with drinking or drugs, and I was even pretty adamantly against it. I was raised with a pretty fundamental Christian background, and I had always sort of seen it negatively and was always pretty against it. But when she passed away, I couldn’t come to terms with the fact that she was gone, and I was only 18 and still had a life to live.”

For the next year and a half, he tried to find that acceptance. He took solace in knowing that Adrienne was in a better place, but going through life without her seemed too much for his young mind to handle. It was at a party back home in Illinois that he tried drinking for the first time, and it was love at first taste, he said.

“I was always somebody who drank to get drunk,” he said. “Part of that was the escapism I needed; part of it was that I was never taught anything about moderation. When I started drinking, I stayed relatively healthy and controlled in the sense that it was only happening every two weeks, but being in music school, when you throw into the equation the fact that all your heroes are glorified substance abusers; an extremely rigorous schedule; and the fact that didn’t have time to grieve — it went downhill pretty quick.”

Class absences mounted, and Belmont staff gently nudged him toward withdrawal for the semester to focus on his mental health. Instead, he turned to drinking more. His consumption grew from weekends to every few days to every day.

“I remember Joe Walsh said one time, ‘I got drunk once, and it lasted for 19 years,’” he said with a chuckle. “I was like that. At any moment I could, I was.”

Fixing A Hole

“I was completely spiraling by the time I got out of school, just drunk 24/7,” he said. “There are months of my life from that year that are just gone.”

Driving home to St. Louis, he stopped for a pint of liquor, crashed his car and blew a .3 on the breathalyzer test, earning him a DUI charge. It was textbook “unmanageability and insanity,” he said, but it still wasn’t enough to get him sober. Oh, he paid it all of the usual lip service, even promising his new girlfriend that he would quit, but within a week, he was drinking again, he said.

“Ultimately, what ended up happening was that I really think I had a death wish,” he said. “I was trying to kill myself because I was so caught up in survivor’s guilt. Any time something good would happen, I’d fall apart, and I was locked into the idea that all my heroes, guys like (Edgar Allen) Poe and (Robert) Burns, had to have tragedy. I was obsessed with the idea of drinking and drugging myself to death.”

It was Adrienne, ironically, that prompted him to finally get sober. They both loved The Beatles, and after her death, he organized an annual memorial concert in which he and friends in the Belleville, Ill., music scene would play the band’s songs in her honor. It was at one of those, in front of her friends and family, that he demonstrated just how bad his problem was.

“I got hammered during the day, then I got up in front of everyone,” he said. “I couldn’t speak, I could barely stand up, and that was the moment I had to come to terms with the fact that my addiction was not something that was glorifying her memory. That’s when I decided to go to Cumberland Heights for the first time.”

Let It Be

“I was at a point where real healing actually started happening,” he said. “I could face my grief and accept life on life’s terms. Before, I couldn’t accept or forgive, and that’s what had been killing me.”

He started working at Michael’s, the arts and crafts chain, while living in a halfway house, and he rebuilt the connection with Bryan Clark, the owner of his label, Rainfeather Records. Coming back to music, he added, wasn’t just a rebirth of his talent; it was an entirely new relationship altogether.

“I think what I did musically was that I allowed myself to really step back, not pick up the guitar for a few months, work that job, go to meetings all the time and really decide if music was what I wanted to do anymore,” he said. “It had been so long since I had decided music was a joyful thing to me.”

It was, he discovered, and the words his recovery inspired eventually became his most recent album, “Second Wind.” It’s a beautifully stark and languid piece of Americana, with Dennis’ songwriting reminiscent of Taylor Goldsmith of Dawes, his world-weary voice conveying every trembling worry and every awestruck wonder that his newly mended heart can manage.

“From there, things got wildly better,” he said. “It taught me to trust the process with music, and it really allowed me to come to terms with who I was in that place, and where I was at that time.”

He’s currently wrapping up work on a new album, “Mortal Flames,” that he hopes to release in the new year. He continues to work his recovery, and he returns regularly to Cumberland Heights, where fellow recovering musicians like John McAndrew and Bogie Bowles helped him to get sober. And he continues to write songs, from an honest and true place.

“One of the things that’s been so key to me in my sobriety is that when the record came out, I chose to be as transparent as possible,” he said. “It really helped me to forgive people in my path because they’re human, and it helped me realize how many people are struggling.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories