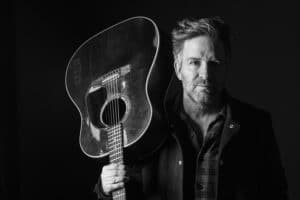

Singer-songwriter Scott Miller: ‘Being sober is always your best chance’

Courtesy of Tasha Thomas

Singer-songwriter Scott Miller: 'Being sober is always your best chance'

Out in the fields of the family farm nestled in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, 70 cows roam 200 acres of property. He’s got hay to cut and elderly parents to take care of, including a father who suffered a stroke last fall. The record he released two weeks after that hasn’t gotten the support it needed from steady touring because of Miller’s commitments, and having to place his music career on the back burner because of family and farm obligations is a source of frustration, he tells The Ties That Bind Us.

On top of all that, it’s been too long, he adds, since he sought respite in a 12 Step meeting.

“Sometimes you pedal, and sometimes you coast, but I know that if I got and sit for that one hour, I’ll be better off for it,” he says. “It’s that safe place, where you don’t feel alone, and everybody’s telling your story. To go into a meeting and just hear somebody talk from their gut, it doesn’t matter what they’re spewing — that is as close to God as I can get.

“When you find that right meeting, and you have that moment where you realize you’re not alone, that’s what it’s all about. As diverse as this disease is with how it affects the poor, the rich, whatever — it’s basically all the same. It’s all fear and resentment, and the key is facing it and acknowledging it. You don’t even have to conquer it.”

He made a mess of this town

Courtesy of Tasha Thomas

Like most addicts and alcoholics, however, Miller did his best to beat that fear into submission with the business end of a liquor bottle. It wasn’t a long battle — after all, he points out wryly, he didn’t start drinking until he was 25 — but it sure was intense.

“I come from a family of alcoholics, and I didn’t want anything to do with alcohol, but I was in such pain — depression, a chemical imbalance, whatever — that when I had that first drink, it worked,” he says. “Alcohol, though, is like your best friend that (messes) with you. Ninety percent of the time, he’s your best buddy, but the other 10, he’s sleeping with your girlfriend, and you keep going back to him.”

Miller’s intellect has always given his songwriting a keener edge than that of many of his Americana peers. He graduated from the College of William and Mary, having focused on American history and Russian studies, and moved to Knoxville, Tenn., in 1990. He played around town as a solo singer-songwriter before launching a new band, The Viceroys, in 1994. After a lawsuit from a similarly named Jamaican band forced the group to change its moniker to The V-Roys, the band started making a name for itself in the East Tennessee scene.

At a time when alt-country and Americana blossomed on college radio and in the indie club underground, The V-Roys were a sharply dressed group of players who excelled at constructing fan-favorite sing-alongs like “Cold Beer Hello” alongside driving road-dog rockers (“Sooner or Later,” “Over the Mountain”) and sentimental sad sack anthems (“Goodnight Loser,” “Lie I Believe”). Maverick country-rocker Steve Earle signed the band to his E Squared label for their 1996 album, “Just Add Ice,” and the guys released one more, “All About Town,” in 1998 before calling it quits a year later.

Drawing on his Virginia roots, Miller put together a backing band, the Commonwealth, and released “Thus Always to Tyrants” in 2001 on the respected roots label Sugar Hill. Other records followed — “Upside/Downside,” “Citation” and “For Crying Out Loud,” before a 17-year affair with alcohol started sputtering to a fitful stop in 2010.

“I started blacking out after two drinks,” he says. “I wasn’t getting crazy, but it’s like your body starts processing alcohol differently, and instead of working, it starts making you this paranoid person. I did what everybody else does — I tried to quit for a month, I tried to just drink beer, and those things never work. I was headed for the same spot we’re all headed for if you’re an alcoholic.”

Scrabble and 'fourth meals'

Courtesy of Tasha Thomas

His moment of clarity occurred in the fall of 2010, when after a three-week tour run from Tampa to Boston, he found himself with a free Sunday. His wife, Thea, was out of town, and he headed over to his favorite Knoxville watering hole, Rooster’s, to watch football and drink.

“I went and sat at the bar and ordered those awesome wings and started putting them away, and I remember looking at that bar back, completely full of liquor, and thinking, ‘I can drink every drop of that right now, and it’s not working,’” he says. “It wasn’t stopping that pain — that indescribable pain where everything hurts, where every feeling hurts, and as I looked up there thinking about how I could drink it all, I could just hear this voice say, ‘Enough!’

“I was hurting so bad, and there was nothing else to try. Nothing else was giving me relief, so what else was there, other than trying to get sober?”

He reached out to a cousin who put him in touch with a substance abuse treatment professional; that individual met Miller as he was 12 hours into alcohol withdrawal; a quick blood pressure check revealed a potential medical crisis — “My BP was 250 over something, and my ears were ringing, and he said, ‘We’ve got to get you to an ER,’” Miller remembers.

Several snapshots stand out of his stay at Blount Memorial Hospital in Maryville, Tenn.: The doctor who gave him a shot in the emergency room and put a comforting hand on Miller’s shoulder, telling him it was going to be OK; striking up fast-and-furious friendships with the community of addicts, alcoholics and mental health patients in Blount Memorial’s Emotional Health and Recovery Center, eating “fourth meal” bologna sandwiches late at night and playing Scrabble; being prevented from isolating himself by the nurse on the ward.

“I would sit in my room, and she would say all sweetly, ‘Is somebody trying to isolate? You’ve got to get out here!’” he says with a chuckle. “It was the longest seven or 10 days in there; it just seemed like forever, but they’re some of my best memories, too, because of the camaraderie. There was no judgment, and in there, I found my church. It was like, ‘We’re all here; we’ve all given up.’”

After being discharged, he did what his brother-in-law had suggested years prior: He went to meetings, and he held on like a drowning man onto a lone lifeline thrown into churning seas.

“I got out on a Saturday, and that Sunday, I went to a meeting,” he says. “My sister was in recovery for a lot of years before she passed away, and she had married a guy she had met in recovery, and he was the most Zen guy I’d ever met in my life — so I knew that the one good thing about all of this was that there was a path.

“I had been to three or four meetings where I would just sit in the back, and hell, I probably went out and drank afterward. I just wasn’t ready to commit before, but I was then.”

Sobriety > zombies

He took the one piece of advice that’s perhaps given most often as recovery meetings: He kept coming back … and in the process, his life got better. He’s released two albums in sobriety — 2013’s “Big Big World” and last year’s effort — and he got back together with his old V-Roys bandmates for a one-off reunion show in 2011. That same year, he and his wife moved back to Virginia to keep the family farm in operation, and he continues to tour and perform from Texas to the Northeast, as time allows.

“I used to think that you had to achieve this transcendent spot to do your art, but that’s just total horseshit,” he says. “I play better now, and I sing better. My shows are better — and I remember them.”

And he’s able to be of service to other addicts and alcoholics. He tells the story of a friend who’s currently struggling, and Miller knows the best place to send him.

“I’ve been trying to get him to go to a meeting,” he says. “I tell him to go in and sit in the back and just listen, to go in there until somebody tells his story, because somebody is gonna tell his story! That’s how it happened with me, and you find some of that in the Big Book, something you’ll read and go, ‘That’s me!’”

These days, with his commitments to the cows and to his parents and to his wife, that lifeline sometimes feels tenuous and frayed. His guitar seems to gather too much dust; the ink ribbon on his old typewriter, on which he writes his songs, seems to go longer and longer periods without filling the house with the sound of clacking keys. He’s easier to feel restlessness, irritability and discontent, and that’s when he knows, he says, exactly what he needs.

“A meeting! I need a meeting, because the threat of me drinking is not due to some catastrophic event, where I shakily stumble into a bar and order a shot — it’s getting overwhelmed and screwed up in the head and thinking I deserve it,” he says. “In the beginning, being the smart ass I am, I would joke that ‘all Steps are null and void in the event of a zombie apocalypse.’

“But you know what? No! if there’s a zombie apocalypse, my best chance of survival is to be sober and clearheaded, and that applies to whatever problem I’m facing. Being sober is always your best chance.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories