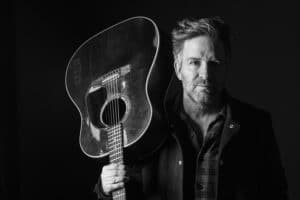

Singer-songwriter Tommy Womack: ‘I’m a cat on my ninth life’

Courtesy of Stacie Huckeba

Singer-songwriter Tommy Womack: 'I'm a cat on my ninth life'

Like a lot of recovering addicts and alcoholics who have put a little distance between themselves and their last use, singer-songwriter Tommy Womack can appreciate that his partying days included plenty of fun and comfort.

At first, anyway. But like those with whom he shares a bond of recovery, there came a time in his own life when addiction, sadistic fisherman that it is, jerked the line, set the hook and began to reel Womack toward the bitter ends: jails, institutions and death.

He still remembers that first buzz from a couple of beers, and the courage it gave him to talk to a girl and look her in the eye. He remembers the first time he smoked pot, and how after an initial 15 minutes of discomfort, he was transported back to his childhood.

“I hated myself and wanted to die for about 15 minutes, and then suddenly this dam burst, and I felt like I was 5 years old again, when I used to crawl into mom and dad’s bed while Dean Martin was on,” he says. “I wasn’t allowed to watch it, because Dean was naughty, but the most secure, safe feeling in the world was being in their bed, with the light in the hallway on and the door open and Dean Martin singing in the family room.

“Later on, I discovered it was really a lot of fun to listen to records while you’re stoned. And later on from that, I learned it was really fun to play guitar on stage when you’re stoned. It worked for me for a long time, because pot agreed with me more than alcohol did, but when it turns on you, it’s a bitch. I’ve had pot psychosis before, and it isn’t fun. You’re scared all the time. I think people might think it’s like a split personality, and you’re happy being one of your different personalities, but it’s not that way at all. It’s a very scary trip to take.”

Sailing the seas of Cheese

Courtesy of Stacie Huckeba

A Kentucky boy who achieved a modicum of national fame with the post-punk band Government Cheese, which got some brief MTV airplay, Womack fell into a well-respected circle of artists after moving to Nashville that may not be household names, but they sure command respect among music aficionados. Guys like Todd Snider, John Prine, Jason Ringenberg and Will Kimbrough have all sang Womack’s praises over the years, and he’s put out a half-dozen solo albums that won accolades in the Nashville Scene.

His most recent album, “Namaste,” was released in 2016. It’s the first solo record he’s made while sober, and on it, he tackles a number of topics, all of them wrapped in a shroud of wonder and wry observation and Womack’s trademark wit. Few artists, for example, can pull off a song like “When Country Singers Were Ugly,” which is a rather startling song title but, upon further reflection, is spot on: “Willie was nothing to look at, all Waylon inspired was fear, country singers were tough on the eyes and not so often the ears ...”

Underneath it all, however, is an attitude of gratitude, to borrow a term thrown around in the rooms of recovery. He didn’t set out to make it that way, but it’s almost impossible to keep out of the songs when the writer himself feels it so keenly.

“It’s a glorious way to live,” he says. “I still get a kick out of waking up without a hangover — that never gets old! — and I like the brain that I have now. My short-term memory is really poor, and I get lost in the middle of guitar leads sometimes; I have brain damage, but at least it’s not progressing any further than it was. And because the brain can rewire itself, at 55, maybe I have enough vim and vigor in myself to maybe rewire my brain and get a better memory!

“The biggest thing is that I keep out of my own head much more than I ever did. I’m there to listen to other people with their problems. I used to be a terrible listener; now, I’m pretty good at it, if I say so myself. And it does me a world of good. Talking to them helps keep me sober.”

There was a time, however, when he was the one with the problems. More than a decade ago, he started using cocaine regularly, and the wheels quickly came off. He had to be revived in an ambulance once, he said, and that still didn’t deter his addiction.

“Cocaine, that’s evil (stuff), man,” he says. “Alcohol and pot are nefarious substances to me and others, for sure, but cocaine’s in a different category. It just grabs ahold of your psyche, and it becomes two different kinds of days — the days you have blow, and the day that you don’t.

“I remember spending $200 on it one time at 3 a.m. in Sylvan Park in Nashville, and I remember vaguely thinking to myself, ‘This is not good, Tommy. This is no way to be.’ But the thought of getting cocaine up my nose at the time was more overwhelming.”

The end of the road

“We did three gigs: The first one was great; the second one, I ate a hash brownie, and Marshall said I was funny as hell but not so great,” he says. “The third one, Marshall and I were going to trade songs back and forth on acoustic guitar, but as soon as I got on stage, she leaned over and whispered, ‘Are you alright?’ ‘Sure! I’m fine!’ But I remember the grimaces on her face as I tried to join in on guitar with her, sounding every bit like you would expect someone to sound on rhythm guitar if they’re on Xanax and tequila.”

The next day, he woke up hungover and started drinking as soon as he got on the plane, destined for the Telluride Americana showcase in Colorado. By the time he got to the bed-and-breakfast, he’d been throwing back booze most of the day, but then the treatment center called: His insurance had been approved.

“I didn’t have any alcohol there, and I didn’t go get any, and I haven’t had any since,” he says. “I’ll have six years on July 18. And once I gave up alcohol, it was easy; it was a miracle. I just gave it all up. I go to meetings rarely, and I call my sponsor rarely, and I haven’t read all the literature, but I don’t drink. I don’t go out and buy pot. I don’t go to Kentucky to cop pills at 10 in the morning when I’m supposed to be at work.

“I’m a cat on my ninth life, and so many things have happened to me that it is, at last and thank God, clear to me that I can’t do that anymore. I’ve lost the desire to drink along the way, and I’m happy, joyous and free, for the most part.”

There have been tough times: He’s survived a battle with cancer, and even though he’s in remission, he’s still undergoing preventative treatments for the next three years. He’s also celebrated some milestones, including the recent completion of a new live album and his second book, tentatively titled “Say This Life and Let It Be Enough for Once,” which he describes as a prequel and a sequel to his first one, “Cheese Chronicles.” He’s enjoying the freedom of being an independent artist, and though the work is hard when there is no major label money to prop him up, that freedom he’s found through sobriety extends to all areas of his life.

And, he adds, it’s available to anyone.

“Go to meetings; don’t use; work the Steps,” he says. “It does work. “I’ve told people who come to me to just surrender, and when somebody says they don’t know how, I tell them, ‘You surrender when you stop fighting, and you know you’ve hit your bottom when you stop digging.’

“Addiction and alcohol, they’re like digging a hole. You’re digging, and you’re shoveling dirt up above your head out the top, and you keep digging until you’re so far down you can’t reach the edge of the hole above your head. Someone has to come along and grab you by the arms and pull you out, and for the rest of your life, you’re standing there with your heels hanging back over the hole, and the only way you can stay out is to keep clasping hold of somebody in front of you who keeps you from falling back.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories